edited by Martin Walsh

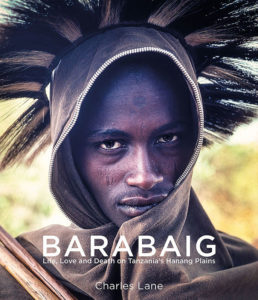

BARABAIG: LIFE, LOVE AND DEATH ON TANZANIA’S HANANG PLAINS. Charles Lane. River Books, Bangkok, 2017. 264 pp., 156 illustrations (hardback). ISBN 978-6-1673-3985-6. £40.00.

Land grabbing, the large-scale acquisition of land for agricultural and other forms of investment, is, quite literally, big business in Africa. Dubbed ‘the new scramble for Africa’, this is most often associated nowadays with Chinese commercial interventions on the continent, though it also takes many other forms, some driven by transnational corporations. At national level, it typically involves collusion between powerful government actors and private sector interests, especially when one has captured or is manipulating the other. Tanzania, alas, is no exception, and has its own sorry history of land and conservation grabs, including ongoing examples that have featured in this bulletin. Following land distribution in Zanzibar and forced ‘villagisation’ on the mainland, the single most significant land alienation to make international news was the eviction of Barabaig livestock herders from their pastures in Hanang District to make way for a Canadian aid-funded wheat growing scheme. The negative impacts of this were documented and brought to the world’s attention by Charles Lane, an Australian researcher who first came to Tanzania in the mid-1970s to work as a volunteer and aid worker. Lane had a long association with the country before he chose the Barabaig as the subject of his University of Sussex PhD, a choice inspired in part by an article by Oxfam Press Officer Derek Warren (‘Aid grows a crop of problems’, The Guardian, 2 December 1983).

As its schmaltzy subtitle suggests, Barabaig is very different in style from Lane’s earlier writing about the people of the Hanang Plains and the campaign to redress the wrongs done to them [See TA 24, 35, 47, 51 and 57]. “This is the story of my time with the Barabaig. Not the outcome of my academic research, but a personal account of warmth and wonder, humour and humility, gallantry and gore. I tell it for the Barabaig, for they deserve to have it told. […] They need to be better understood by those who have condemned them as killers and aimless wanderers unworthy of attention. Indeed, the whole world needs to know about the Barabaig, their ancient culture and way of life before it is lost forever. In telling this tale, I hope I have done them justice.”

Barabaig opens with a double foreword by the Director of Survival International, Stephen Corry, and Guardian journalist George Monbiot. Following Lane’s introduction, the text is divided into three main parts. The first two, ‘Early Days’ and ‘Becoming Barabaig’, are lavishly illustrated by photographs from Lane’s fieldwork, and describe his introduction to Barabaig life and some of the most striking elements of their social life in the late 1980s. Lane doesn’t gloss over his cultural naiveté, and there are plenty of self-deprecating anecdotes of the kind that fill anthropologists’ conversations and memoirs, including perhaps too much information about toilet habits.

The third part, ‘Fight for Rights’, about the struggle on behalf of the Barabaig, was the one I enjoyed the most, and I wish that it had come sooner and occupied more of the text. Lane is refreshingly honest about the successes and failures of the campaign and legal proceedings, while a postscript summarises recent developments and his feelings on a return visit with his family. Barabaig isn’t the first coffee-table-plus-campaign book that has been written about a beleaguered indigenous group in Tanzania, and presumably won’t be the last. I’m not a fan of the hybrid format and its uncomfortable relationship with exoticising and ‘white saviour’ narratives, but hope that it does lead more readers to engage with this and other campaigns against the land grabbing that is blighting so many lives. I certainly finished reading this handsome volume wanting to know more, not to mention wishing that I had Charles Lane’s campaigning instincts and flair.

Martin Walsh

Martin Walsh is the Book Reviews Editor of Tanzanian Affairs.

INCREASING PRODUCTION FROM THE LAND: A SOURCEBOOK ON AGRICULTURE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS IN EAST AFRICA. Andrew Coulson, Antony Ellman and Emmanuel Reuben Mbiha. Mkuki na Nyota, Dar es salaam, 2018. 294 pp. (paperback). ISBN 978-998708-156-356-5. £30.00 (Available from A.C. Coulson, 8 Innage Rd, Northfield, Birmingham B31 2DX, for £20.00).

This is a very important contribution to any discussion of agriculture, food and rural policy in Tanzania. The quest for a sound agricultural strategy has been a key theme in Tanzania since independence, but a really effective and sustained strategy has proved elusive. As this book shows, the enthusiasm of the post-independence government for mechanised settlement schemes quickly ran into the ground in the late 1960s, and by the mid-1970s had been replaced by very large-scale ‘villagisation’ in which at least five million people moved into ‘ujamaa’ villages. In turn this strategy was more or less abandoned in the late 1980s as the World Bank and other donors’ insistence on total privatisation became the dominant theme. The net result in 2018 is an unsatisfactory mix dominated by large- to medium-scale companies and small, mainly independent farmers.

It is the latter who are the subject of this book, which does a remarkable job in identifying and explaining the constraints and opportunities which small farmers face. This analysis goes on to discuss ways forward from the farmers’ perspective, a very rare approach seldom achieved in the many books and pamphlets on African agriculture published over the last fifty years. It is in the tradition of William Allen’s pathbreaking The African Husbandman (1965).

The target audience is students and young practitioners in agriculture in Tanzania and so there are several chapters devoted to the factors of production and basic explanations of the limits to output. However, they are interpolated with fascinating case studies of fifteen individual projects – from the Dakawa Rice Farm, to the Upper Kitete Co-operative, and the Tanga Fresh (dairy) project. These really tell the story of what has worked and what has failed, not neglecting to explain that some success stories – such as potatoes in Njombe

– have been driven by farmers largely on a ‘farmer to farmer’ basis. These cases should make the book of interest to a wider audience of policy makers in government and the donor community.

The impact of new research and technology is a recurring theme. Irrigation is considered in its various forms from low key stream diversion to trickle (or drip) irrigation. Whilst several of these are rated as one of the keys to the future, their limits, set by the physical context, are also recognised. There is a challenging chapter on agricultural research and the role of local and international (e.g. IITA) research centres and their limited impact, mainly ascribed to a lack of mechanisms for dissemination (a debatable point). Scepticism is applied to the role of genetically modified crops which are perceived as being a largely corporate product, a position which downplays the role of CGIAR centres in developing GM crops and the fact that this work is funded by a large range of donors including philanthropic foundations quite divorced from companies.

The book recognises very effectively the external constraints on farmers and points out that the majority of small-scale farmers have at least one family member working in the local economy on either an informal or formal basis. Even with this supplementary income, small farms need to access marketing, credit and ‘extension’ advice – and seldom obtain all three, a major failure of government policy.

It suggests that female-headed households do not necessarily earn lower incomes, in food or cash, than male-headed households and indicates that this distinction, widely considered to be valid in the past, is now breaking down.

The message of this book is that farmers should adopt a blend of proven traditional agricultural technologies (such as intercropping) and modern strategies which conserve the soil (notably conservation agriculture) and new variations of cropping systems which build in trap crops and intercrops to deter pests. Systems which integrate livestock and crops are rightly considered to be essential. At a political level, strategy should be geared to integrating public health and nutrition into food and agricultural policy – as is increasingly accepted worldwide. These issues should make the book of interest to a wider audience of policy makers in government and the donor community.

The analysis and recommendations are clearly applicable across a range of countries, although readers outside Tanzania may be reluctant to engage with the specific case studies. But the authors, all with deep experience, have created a highly readable book which deserves to have a real impact at the ‘farmer level’ – always their objective.

Laurence Cockcroft

Laurence Cockcroft is a development economist who has worked particularly on African agricultural issues since 1966, including work for DevPan and TRDB in Dar es salaam in the early 1970s. From 1985 to 2012 he was responsible for the programme of the Gatsby Charitable Foundation in Africa. He is also a co-founder of Transparency International and was Chairman of its UK Chapter from 2000-08 and has written two books on international corruption.

LEADERSHIP AND CONFLICT IN AFRICAN CHURCHES: THE ANGLICAN EXPERIENCE. Mkunga H.P. Mtingele. Peter Lang, New York, Bern, 2017. xxii + 266 pp. (hardback). ISBN 978-1-4331-3294-0. £69.95.

If abuse occurs within a community, should it be covered up to preserve the reputation of the community, or be exposed to deter recurrence? A highly topical question, and Dr Mkunga Mtingele opts for the latter course in this book: ‘African leaders have to change their way of thinking and their style of leadership. Change will not come if the truth is not told.’

His study tells the truth about six conflicts relating to leadership within the Anglican Church of Tanzania (ACT), with occasional comparisons with other countries. His main case-study concerns the marginalisation of the Sukuma, the biggest tribe in Tanzania, in the diocese based in Mwanza. He is well qualified to speak on this topic, with his legal training, and twelve years as Executive Secretary of the ACT, followed by international experience with the United Bible Societies. He surveys sociological analyses of leadership and conflict in the first three chapters and uses them to interpret his field research.

He identifies numerous roots of such conflicts, beginning with the superior attitude to Africans taken by many colonial rulers and Western missionaries and often inherited by their indigenous successors in leadership. When chiefs were abolished in 1963, it was easy for local bishops to step seamlessly into their shoes, at least in the minds of their fellow tribespeople – and people were demanding a bishop of their own tribe which led to conflict in regions of mixed ethnicity. Tribalism seems worse in the church than in the nation.

Imported church traditions also led to conflict, though to a lesser degree, between evangelicals in the hinterland and Anglo-catholics at the coast, though there were also examples of warm partnership. Mtingele describes what he calls ‘the Episcopal-Syndrome’ as ‘ambition for status, wealth, authority and power (SWAP)’. It creates authoritarian bishops and fearful, sycophantic underlings, leading to loss of trust and to conflict. Many ACT clergy live in abject poverty – no wonder they aspire to be elected bishop and may go to any lengths to achieve it – the polar opposite of the model of Jesus Christ. The author resisted many attempts to make him a bishop – no doubt disillusioned by the episcopal models he met. This reviewer believes Mtingele’s research is relevant to Anglicans everywhere. Conflict was aggravated by accusations of witchcraft; by the silence of lay people when clergy were fighting one another; by the inadequacy of diocesan constitutions; and by the use of adversarial methods rather than the African tradition of decision by consensus.

The conflicts he describes, often involving excessive violence, were a public disgrace, emptied the churches, reduced domestic income and international aid and diverted the church from its mission – yet paradoxically sometimes created new, smaller Christian groups more in touch with their immediate locality, leading to growth.

After pages of gloomy stories, Mtingele concludes with some gems of radical recommendations: better working conditions for clergy; centralised payment of their stipends; limiting tenure of episcopal office; detribalising episcopal appointments; more mergers of the evangelical/catholic traditions. Wisdom indeed, but can a body as conservative as the Anglican Church accept such challenges to the ‘path-dependence’ model which he has shown dominates its practice? The author is working on a basic Swahili version so that his findings may be accessible to Tanzanians. The foreword written by Archbishop Idowu-Fearon of Nigeria calls the book ‘disturbing’ but ‘important … for Africa as a whole and perhaps elsewhere as well.’

This is not, and nor does it claim to be, a balanced picture of the Anglican church. If it were, it would have to mention key figures like Roland Allen, Bishop Tucker of Uganda, Bishop Lucas of Masasi who campaigned vigorously, often fruitlessly, against missionary dominance. It would have to identify the East African Revival (1936 onwards) which, utterly indigenous and independent of, yet influencing, the whole Anglican establishment, brought life and growth to a flawed and sinful church – and knew how to handle conflict. It would also ask if and how the Bible, supposed to be ACT’s guide to life, is used to bring peace.

The many typographical errors are a distraction for the reader and unacceptable in a book at this price.

Roger Bowen

Roger Bowen taught theology in Tanzania from 1965 to 1978 and then at St John’s College, Nottingham. He was editor of the Swahili Theological Textbooks programme and has written Mwongozo wa Waraka kwa Warumi. In retirement he is chairman of the Cambridge Centre for Christianity Worldwide.