by Sheila Farrell

TDT’s priorities: clean water – The scale of the problem

In rural Tanzania, fewer than half of all households have access to clean water within 30 minutes of their homes.

This leads to unnecessarily high rates of gastrointestinal illness, premature mortality especially amongst babies and young children, poor school attendance rates, lost working hours and a lot of time spent fetching water. In 2022 the World Bank estimated that inadequate water and sanitation were costing Tanzania a minimum of US$2.4 billion p.a. or 3.2% of GDP . Almost 70% of these costs were incurred in rural areas.Dirty water, poor sanitation and hygiene are the main causes of gastrointestinal infections like diarrhoea, cholera and hepatitis A & E which pose significant public health risks, especially amongst the under-fives. Although untreated water can be boiled, this does not eliminate all pathogens whilst increasing the already large demand for firewood.

In 2022, diarrhoea ranked fifth among diseases presented to outpatient departments, accounting for 3.7% of all cases. This increases to 8.5% for children under five, even though most cases are treated at home and therefore go unrecorded.

Studies suggest that access to clean water reduces the incidence of diarrhoea by 52%, compared with improved sanitation (24%) and more use of handwashing (30%) . This is why the provision of clean water to rural communities has become one of TDT’s top priorities.

Poor water and sanitation are responsible for an estimated 31,000 deaths in Tanzania each year, of which 18,500 are children. Pregnant women are particularly susceptible to waterborne infections, which contribute to Tanzania’s high rate of stillbirths – 19 per 1,000 births compared with only 3.2 per 1,000 births in the UK – and low birth weights. Children face cognitive deficits, stunting, and a reduction in lifetime earnings due to their shortened learning time at school, whether this is due to absenteeism caused by illness or school time spent carrying water. Even when physically present their ability to learn may be undermined by debilitating waterborne diseases that result in poor digestion of food.

For adults, the World Bank estimates for Tanzania as a whole that water and sanitation related diseases cause the loss of at least six million working days each year, with a further 1.1bn hours lost travelling to fetch water. During the dry season the distance that rural households have to travel to reach any water source – clean or dirty – is approximately doubled as rivers and ponds dry up. Climate change, by extending the length of the dry season, is already making this situation noticeably worse.

The role of the public sector

In 2006 Tanzania launched its Water Sector Development Program (WSDP). Across three phases, this had a total budget of around US$10bn, although the second half of the programme has been characterised by serious under-spending as support from international donors has become more difficult to secure.

Actual government spending on WASH projects has been around 2.53.0% of its budget before debt servicing. However, only 20-25% of the water budget has been spent on explicitly rural projects despite 60-65 % of Tanzania’s population living in rural areas.

This is because urban water systems are expensive, politically visible, and better equipped to absorb big capital budgets, which makes them more attractive to the international donors who have funded around half of the WSDP.

Originally most WSDP projects in rural areas were implemented by small local authorities, with patchy results. Common failings were:

•The high proportion of rural water points falling out of use due to lack of maintenance.

•Weak post-construction support.

•Limited technical knowledge of water engineering within local authorities.

•Affordability and revenue collection issues.

Partly to address these concerns, in 2019 the government created the Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Agency (RUWASA). Instead of the large piped-water and storage systems found in urban areas, RUWASA focuses on boreholes, gravity-fed sources and small piped-water networks, as well as the rehabilitation of neglected water points that have fallen into disuse.

It works closely with community-based organisations, providing technical assistance to ensure that schemes remain operational over time, whilst devolving management responsibility to local communities as far as is practical. RUWASA also provides hygiene training to ensure that the benefits of clean water are not wasted.

Because RUWASA is still building up its operational capacity, it is difficult to assess how much difference it has made. Community management of water resources has been strengthened in some towns and villages and there appears to have been an increase in the proportion of Tanzania’s water budget going to rural areas. This reflects not only RUWASA’s ability to attract funding from international donors such as the World Bank, GIZ (Germany) and Enabel (Belgium) but also its willingness to work alongside NGOs like Water Mission and WaterAid. TDT has also benefitted from RUWASA’s technical assistance when sponsoring water projects in rural areas.

Nevertheless, many households in rural Tanzania still have no access to clean water and government funding alone is insufficient to rectify this. This is why clean water projects have accounted for an increasing proportion of TDT’s own expenditure in recent years.

TDT’s water projects

On average just under half of TDT’s annual income over the last four years has been spent on clean water projects. These are of four main types: shallow boreholes, spring protection works, deep boreholes, and rainwater-harvesting/water storage facilities.

Shallow boreholes up to 30m deep are drilled manually and equipped with hand-worked rope pumps. They are simple structures with low maintenance costs, representing excellent value for money at around £1,500 each, and typically serve communities of 1,500-3,000 people. However, the underlying geology is not always favourable, so this type of project has been undertaken mainly in Kasulu District (Kigoma) where TDT’s local partner MvG has now drilled around 180 such bore-holes.

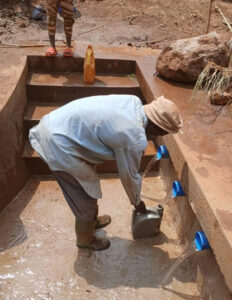

Spring protection schemes filter spring water through gravel beds and channel it into pipes, allowing villagers to fill their buckets from the pipes before the water hits the ground and becomes contaminated. The pipes lead into a concrete basin that takes the overflow (the pipes have no taps) and this is sometimes fenced to restrict animal access. These cost roughly the same as shallow boreholes and serve villages of a similar size, but whereas boreholes can be built close to people’s homes, reducing the amount of time spent carrying water, spring protection works are restricted to places where water reaches the surface naturally. For geological reasons most of TDT’s spring protection projects have been undertaken in Kagera Region to the west of Lake Victoria.

TDT has sponsored relatively few deep boreholes, which can go down to 200m before they reach water. These are more costly, at around £10,000-15,000 per borehole, and require the use of a contractor with expensive mechanical drilling equipment. Because pumping the water up to ground level requires electricity, this type of borehole may require a storage tank to protect villagers against power cuts or allow the use of solar power for pumping. TDT has recently been helping villages with no alternative means of accessing water to develop contracts that will transfer to the contractor more of the risk of not finding water.

Finally, TDT has funded several rainwater harvesting schemes, where water is collected from roofs when it is raining and channelled into storage tanks. These are suitable for small-scale users such as village schools and health centres.

Compared with the scale of the problem, TDT’s contribution is small. But it is providing clean water to villages that would otherwise have to wait many years for it, with low-cost projects that make a big difference to people’s lives. Since 2021-22 we have helped 295,000 people to access clean water. We are grateful to the BTS members who support this work.

References

https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/tanzania/publication/tanzania-economic-update-universal-access-to-water-and-sanitation-could-transform-social-and-economic-development

https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099141002082366224/pdf/P17961001428f80cf0a6700fadf5ecf43ef.pdf