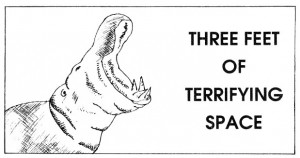

Suddenly, with a speed I did not believe possible for a beast of such vast, barrel-like proportions, a hippopotamus rose beneath us. Its great mouth sprang open and for a second I saw three feet of terrifying space between its gaping jaws, just a foot away from my left leg.

Its jaws closed on the side of the canoe, but its teeth slipped on the plastic. In a flash we were both stabbing the beast with our oars like frenzied Maasai warriors, discouraging the second assault somewhat. Then, seeing clear water, we plunged our paddles into it, shooting the canoe forward and away with an enthusiasm that would have done credit to the best Oxford or Cambridge rowers. We escaped with leaping hearts to the other bank to light a fire and brew a calming pot of tea.

I remembered the words of Sir Samuel White Baker, the explorer, who noted in 1869: “Being charged by an elephant is a new sensation – very absorbing for the time. It would be an excellent relaxation, once a week, for men in high office.” I wondered whether he would say the same of a hippopotamus attack.

We were in the Selous Game Reserve – the largest, and one of the most inaccessible game reserves in the world. The Rufiji River, with a drainage basin larger than the United Kingdom, runs through it to the Indian Ocean. It was this untamed river, which had never before been navigat2d, that we were hoping to canoe on, from source to sea.

Our route to the source was long and complicated. We needed a permit from Dar es Salaam. Our borrowed canoe lay in Zimbabwe and the cheapest air fare took us to Nairobi via Moscow.

We finally arrived at our starting point near Ifakara on a local bus with our canoe on the roof. Within three days the two of us were alone. For nearly four weeks we would not see a single human being in our vast wilderness. However, we would pass about 40,000 of the beautifully ugly, small-brained hippo. Here, along with the largest populations of elephant, lion, leopard and buffalo is the biggest concentration of hippo and crocodile in the world.

We were hoping to supplement our basic supplies, which we had bought in Ifakara, with fish, but our line proved to be too light. We were down to our last cup of maize meal when a large tiger fish leapt into the canoe. Another day we stole three dozen crocodile eggs and grilled baby crocodiles whole. Sometimes the river got too much and we would spend days blundering through the thick, thorny bush with the canoe on our heads and the tsetse fly around us.

In Stieglers Gorge, where the river roars down a series of rushing rapids, and the precipitous sides rise 300-400ft, making escape almost impossible, we capsized twice, nearly losing the canoe and our belongings.

We reached the delta, a 50-mile wide maze of tidal channels, tired and lost. A man carrying 3,000 mangoes towards the Indian Ocean in a dugout canoe appeared and led us through the final stretch, 22 hours of non-stop canoeing.

Eventually we reached the Indian Ocean, where we sailed to Dar es Salaam in an open 40ft dhow. As I lay there that night, I echoed the words of Wilfred Thesiger: “I learnt the satisfaction that comes from hardship and the pleasure that springs from abstinence; the contentment of a full belly; the taste of clean water; the ecstasy of surrender when the craving for sleep becomes a torment.”

I wondered how long it would be before I would have to be learning these things again.

Ben Freeth

(This article appeared first in The Times Magazine – Editor)