by Martin Walsh

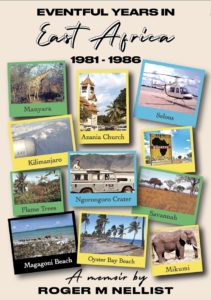

EVENTUFUL YEARS IN EAST AFRICA: 1981-1986. Roger M. Nellist. Privately printed (Book Printing UK, Peterborough), 2021. ix + 338 pp. (No ISBN no.) (paperback). Copies available from the author rogermnellist@ hotmail.com

Avid readers of Tanzanian Affairs will know Roger Nellist as a regular contributor who covered the Energy & Minerals brief for many years until he stepped aside in 2021 to spend more time on his own projects. The first fruits of this have now been published in the form a memoir of his five years in Tanzania working as an economic adviser to the Ministry of Water, Energy and Minerals (as it was called for a time) in Dar es Salaam. He arrived in July 1981 as a keen 29-year-old with seven years’ experience in Whitehall, and left in July 1986 to take up a London-based job with his employer, the Commonwealth Secretariat.

With the economy in dire straits, this was an extraordinarily challenging time for the country and its citizens. The prosperity promised by independence and then state socialism had clearly failed to materialise for the majority of people, who often struggled to obtain basic goods and services without mobilising personal networks, resorting to the black market, or engaging in other forms of corruption. This was the Tanzania I encountered myself when I flew into Dar for the first time (I had to bribe my way in), and the grim backdrop to Roger Nellist’s memoir, evident in many of the anecdotes that he tells.

Tanzania’s parlous economic state and the government’s pressing need to turn this around was also the reason for his presence. The core of his book describes his close work with the minister, Al Noor (‘Nick’) Kassum, and other colleagues to ensure that Tanzania gained as much benefit as it could from agreements with international companies to exploit its natural gas and other resources. This laid the groundwork for the development of the energy sector in the years of economic liberalisation to come, and is work that the author is rightly proud of and was subsequently honoured for.

As an autobiographical account written primarily for family and friends, this is far from being an academic text, and there is a lot more in it than an outline of the work that its author evidently excelled at. We learn a lot about his friendships and activities outside the office and about expatriate life in general, as well as his travels and the later development of his career. The five thematic parts and similarly thematic chapters make it easy to follow different topics (I began with the chapters about Zanzibar in Part Two), as does a detailed index (which is not included in the page count given above).

This is one of the most interesting memoirs of its kind that I’ve read, full of striking detail drawn from the diaries and other records that the author diligently kept, and illustrated by numerous colour photographs that bring the text to life. For me it provided insights into a social and cultural world that I only caught passing glimpses of when living in a village more than a day’s journey from Dar. It also reminded me of my own subsequent experiences as an expat, including the sights and sounds and smells of the city that I got to know in later decades, when those bare shelves, oddly empty streets and furtive transactions were becoming a distant memory.

Eventful Years in East Africa is a very welcome contribution to its genre and to our understanding of a little-studied period and developments in Tanzania’s modern history. When future monographs and papers are written about expatriate advisers and their impacts in postcolonial Tanzania, this book will surely be prominent among their sources. It deserves to be more widely read and I hope that plans to make it more readily available to a larger audience come to pass.

Martin Walsh Martin Walsh is the Book Reviews Editor of Tanzanian Affairs. He first went to live in Tanzania in 1980, when he was 22.

LETTERS FROM THE NEW AFRICA 1961-1966: SIXTY YEARS ON. Tim Brooke. Privately printed (Buy My Print, Coventry), 2021. 150 pp. (paperback). (No ISBN no.). Copies available from the author timb968@gmail. com and pdf free to download at https://timothybrooke.wordpress.com/

Twenty-three-year-old Tim Brooke arrived in Tanganyika in December 1961 to teach at St Joseph’s College, Chidya, a secondary boarding school run by the Universities’ Mission to Central Africa (UMCA) in Masasi Diocese. He stayed there for four years, leaving Tanzania (as it had become) in March 1966. This memoir is based on his letters home from Chidya and elsewhere (though not the New Africa Hotel in Dar, which was my first reading of the title!). Here is the author’s summary:

“In this book I have chosen extracts from my letters particularly to illustrate what it was like to be part of that wave of young people in the 1960s going to Africa from Britain and North America to volunteer. We found ourselves mainly in the rapidly expanding secondary school systems because insufficient local people had been trained to fill all the roles required by a post-colonial society. These young people – with a mixture of idealism, a sense of adventure and a desire that independence should really work – were responding to this time-limited need. There was a sense of Wordsworth’s ‘Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive’.

“The selection aims to give a feel of everyday life at that moment in an African boarding school. They record too attitudes to the growing power of China, my involvement in the East African army mutinies, the legacy of Britain’s Groundnut Scheme and two extraordinary phenomena seen in the night sky. They also bring to life two internationally known Europeans living in the south of the country – Bishop Trevor Huddleston, who by his book ‘Naught for your Comfort’ (Collins 1956) had drawn the world’s attention to the injustices of apartheid, and C.J.P. Ionides, the snake collector. They look above all at what it was like to be living as a European in Tanganyika at the crossover point between colonial status and independence, an amazing time of political and social transition as Tanganyika began to establish itself as a sovereign country in the eyes of both its own people and the rest of the world.”

Decolonisation and its challenges loom large in Tim Brooke’s letters: the stuttering progress towards Africanisation in the school and church(es); the powerful example of Trevor Huddleston and his influence on the author and others around him; and the political and other events at national and international level that were happening at the same time. It is fascinating to read of the different ways in which all this impacts on the young letter-writer and his family (he had a younger brother in Southern Rhodesia). It becomes intensely personal when he is wrongly arrested for embezzlement – thanks to an erratic headmaster who is later found to have been opening his teachers’ mail before hiding it in a bedroom cupboard. The tension in this episode is palpable, until a swarm of angry bees provides Tim with a get-out-of-gaol-free card, following which the Bishop and others come to his rescue.

In addition to ‘Bishop Trevor’ and ‘Iodine’, whose snake-catching operation is described in detail, the letters introduce us to a large cast of colourful characters in the school, diocese, and further afield. Many went on to have long and distinguished careers, as we learn from thumbnail sketches at the end of the book. Readers may be familiar with some of them, includes the likes of Tim Yeo, the future Conservative MP, reclining on the grass in a group photograph, and the still-active Cambridge historians John Iliffe and John Lonsdale, helping to shake up the study of history at the University of Dar es Salaam, where the author was attending a course run by Terence Ranger – who also appears in a photograph with Louis Leakey.

Teaching at Chidya and all it entailed was evidently a formative experience for the author, and we can see his worldview evolving as the correspondence progresses. The letters have been skilfully selected and edited, with just the right amount of explanation added. Researchers interested in the full collection of unedited missives can find them in the USPG archive (‘Papers of the United Society for the Propagation of the Gospel’) in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. If this readily accessible volume of extracts is anything to go by, they’ll be well worth the read.

Martin Walsh

A STONE IN THE ROAD: TWO YEARS IN SOUTHERN TANZANIA.

James French. Privately printed (Tellwell Talent, Victoria, British Columbia), 2017. 212 pp. (paperback). ISBN 978-1-77370-251-3. £15.21 (pbk); £5.30 (e-book).

Jim French and his then-wife Marlyn pitched up at St Joseph’s College in Chidya in September 1967, one and a half years after Tim Brooke (see the previous review) had left this UMCA-supported secondary boarding school in Masasi Diocese. They were relatively experienced Canadian volunteers, having already trained as teachers and taught in Canada, while Jim had just completed an M.A. in English at the University of Sussex. Their contract with the Canadian Voluntary Service Overseas (CUSO) was for a two-year stint: Marlyn left a little early for family reasons, Jim in July 1969, when the national programme of Africanisation finally saw all the remaining non-Tanzanian staff replaced.

A Stone in the Road is a well-crafted memoir of their time in Chidya and occasional travels away from the school. It is nicely illustrated with photographs and maps and informed by letters written at the time, in particular regular aerogrammes sent by Marlyn to her parents in Canada. Jim French has woven a fine narrative out of these materials and his and others’ recollections, moving seamlessly back and forth in time as its major themes unfold. The result is a compelling account of their experiences and especially life at Chidya, with all of its ups and downs. The stone of the book’s title is a buried rock that frequently catches vehicles negotiating the 18-mile track between Masasi and Chidya. The school is quite literally at the end of the road, sometimes cut-off altogether by heavy seasonal rains.

The relative isolation of Chidya pervades this memoir and the mood of its writer. It seems to magnify the minutiae of life on the school compound, not least the medical and other hazards that horrify the author and the social frictions that trouble him at work. At least they can afford to get away from time to time. Even so, on their road trips they encounter obstacles of the kind that many budget travellers will be all too familiar with, especially those who can recall the less well-connected world of the past. It’s a testimony to the author’s skill in evoking their travails that I was swept along and struggled to contain the anxiety that his writing induced, amply supplemented by memories of my own bad trips.

Back in Chidya, things appear to get worse as the end of the two years approaches. One of their next-door neighbours, a teacher from India, stops communicating with Jim and Marlyn because they had forgotten to invite him to a lively party. Jim suspects that some students resent him because he’s the only teacher who confiscates the forbidden open-flame tin lamps that they smuggle in to read by (and cram for exams) when they’re supposed to be asleep. One of these students misinterprets something he says in class and spreads the word that he’s a racist, later calling him “Mzungu” (“Whitey”) as he walks past. Jim is shocked and mortified. Marlyn has to rush back to Canada because her father is ill. Left alone for the last few months, Jim eventually takes to the bottle. I might have the order of these events wrong, or be exaggerating, but you get the picture.

Of course, the author knows what he’s doing. Referring to his hangovers, he confesses “I was enacting my own version of Somerset Maugham’s story, “An Outpost of Progress,” in which the two colonials in an isolated post end up in a hopeless fist fight. I was fighting with Jim French.” As well as references to Joseph Conrad and Graham Greene, we are also treated to a reconstructed dialogue with students about Macbeth, and are told that their “enthusiasm for Shakespeare was challenged only by their admiration of Chinua Achebe’s novel Things Fall Apart, adopted as the novel for study in January 1969.” Things aren’t always falling apart in this book; there are many moments of happiness and hope, including the removal of that symbolic stone in the road. I very much enjoyed Jim French’s memoir, especially when it drew me into his sometime uneasy world.

Also noticed:

CHINA AND EAST AFRICA: ANCIENT TIES, CONTEMPORARY FLOWS. Chapurukha M. Kusimba, Tiequan Zhu, and Purity Wakabari Kiura (editors). Lexington Books, Lanham, Maryland, 2020. xx + 277 pp. (hardback). ISBN 978-1-4985-7614-7. £81.00.

From the publishers’ website: “China and East Africa: Ancient Ties and Contemporary Flows marks the culmination of a new round of archaeological and historical research on the relations between China and Africa, from the origins to the present. Africa and Asia have always been in constant contact, through land and seas. The contributors to this volume debate and present the results of their research on the very complex and intricate networks of connections that crisscrossed the Indian Ocean and surrounding lands linking Africa to East Asia. A growing number of speakers of Austronesian languages returned to Africa, reaching Madagascar in the early centuries of the Common Era. The diffusion of domesticated plants, like bananas, from New Guinea to South Asia and Africa where phytoliths are dated to the mid-fourth millennium in Uganda and mid-first millennium BCE in southern Cameroon, provide additional evidence on early interactions between Africa and Asia. Africa and Asia have always been in constant contact, through land and seas. Edited by Chapurukha Kusimba, Tiequan Zhu, and Purity Wakabari Kiura, this collection explores different facets of the interaction between China and Africa, from their earliest manifestations to the present and with an eye to the future.”

The focus of this book is on Kenya, but there’s much that will interest students of Tanzanian history, including a chapter by Elgidius Ichumbaki, ‘Unraveling the links between Tanzania’s coast and ancient China’.