by Martin Walsh

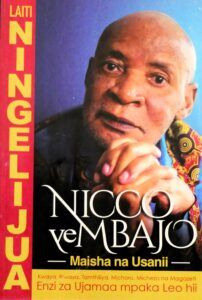

.LAITI NINGELIJUA: MAISHA NA USANII. Nicco ye Mbajo. TuwaKadabra Productions, Dar es Salaam, 2020. 141 pp. (paperback). ISBN: 9789987971091. TSh. 10,000 (available in Tanzania from Elite Bookstore at Mbezi Beach and Kona ya Riwaya Bookshop in Kinondoni, Dar es Salaam. It can also be obtained from the reviewer at uta.reuster@gmail.com.

Nicco ye Mbajo (1950-2021) was a popular Swahili writer and illustrator, cartoonist, editor, and co-founder of the Swahili magazine SANI (established in 1978). He was among the popular Swahili writers of the 1970s and 1980s such as Hammie Rajab, Kajubi Mukajanga, S.A.M. Kitogo, and Ben Mtobwa, who created an extensive body of work that combined entertainment with social criticism. Unbeknownst to many, Mbajo was also the father of the famous SANI cartoons, such as Lodi Lofa (the city loafer), Madenge (the cunning school-boy), Ndumilakuwili (the hypocrite) and Komredi Kipepe (the backward country-bumpkin). They represent certain personality types that the urban environment in Tanzania produced, contrasted with a set of rural characters, who stand for backwardness and simple-mindedness.

Mbajo, however, was also a gifted musician and choir director, who even founded a dance band up-country in the 1970s. His active career as an artist, cultural producer and entrepreneur spanned the period from the 1970s to the 2010s, from Ujamaa to Mageuzi, experiencing and navigating privatisation, liberalisation, and multiparty democracy.

In his autobiography he looks back on this career, which, as the title Laiti Ningelijua (“If I Had Known”) signals, ultimately fell short of what he would have thought possible, given his talents and artistic abilities. The text is a gripping account of Mbajo’s various attempts to make a living through art and culture in Tanzania, which led to some great successes, but always followed by drastic setbacks. In some cases, Mbajo blames his own misjudgements and bad decisions for his failures, which gives his autobiography the character of a confession. In other cases, however, he was affected by political and economic developments over which he had no control.

The first chapters follow chronological order, starting with Mbajo’s childhood in the village where he grew up as one of ten children of a Christian catechist, to whom he credits his artistic talents. At school, his talents were recognized and used for school festivities and political events of the newly independent country.

During his secondary education in Dar es Salaam (1966-1969), Mbajo became an enthusiastic supporter of President Nyerere’s political vision of Ujamaa socialism. He joined TANU’s youth league and composed political propaganda songs. At the same time, he became fascinated with urban music culture, especially the performances of orchestras such as Kilwa Jazz, Dar Jazz, and Safari Trippers. In all his works, he tried to entertain while promoting Ujamaa ideology.

Unfortunately, at that time there was no possibility of formal artistic training in the country. After O-level, Mbajo was selected for training as an agricultural officer and was posted to Tanga in 1972. Yet, he remained true to his artistic inclinations. During college, he played in a jazz band, composed choir songs, and wrote and directed propagandistic theatre plays. He continued his cultural activities in Tanga and became well known in the region. However, as he neglected his professional duties, he was one of the first to be affected by the redundancy of state employees due to budget restrictions in the mid-1970s.

Mbajo’s account of his various attempts to secure an income during the following two years is adventurous. He eventually ended up in Dar es Salaam, where after some time he was employed by the state-owned Printpak printing press as an illustrator and layout artist. Printpak was a hub for publishers of entertainment magazines, almost all of which focused on photo-novels. Seeing a market opportunity, Mbajo developed a magazine featuring comics and cartoons that was based on the Kenyan Joe magazine. Using their initials, together with his partner Saidi Bawji they registered SANI magazine. It became the longest living Swahili entertainment magazine, published until 2020. However, Mbajo was forced out of the company after a short time. This was a crushing blow for him, especially as he had given up his job at Printpak for SANI.

Subsequently, Mbajo founded a new, similar magazine, which he soon published de facto on behalf of Murtazar Alidina, a Tanzanian media entrepreneur of Asian descent, who financed the magazine and paid Mbajo royalties. In dire economic conditions in Tanzania, this businessman took on several authors and so became the engine of popular Swahili magazines and novels, which could be printed in numbers above 10,000 because he was able to distribute them widely. Mbajo published seven novels during that time, which he summarises and puts into context in the fifth chapter of his autobiography. However, the cooperation with Alidina came to an end in 1985, when the latter emigrated to Canada due to the political “anti-economic sabotage” campaign of Prime Minister Sokoine. The publication of popular literature in Tanzania dropped for a while as a result.

Lacking the capital to continue publishing, Mbajo switched to working as a choirmaster for a number of choirs, mainly from Lutheran congregations. He reports on this in the sixth chapter, which also includes songs he composed himself. In particular, he focuses on the choir competitions which are an integral part of the choir culture in Tanzania and in which his choirs had often been successful. In addition, they took him on trips to neighbouring countries and even to the United States. Eventually, he worked as editor of the church magazine Pwani na Bara (“Coast and Hinterland”) until he retired in 2005.

Mbajo’s autobiography is a unique testimony of an important producer of Tanzanian popular culture in the 20th century and a well written literary work that captivates with its self-critical attitude. It shows first-hand how difficult it was to earn a living as an independent artist in socialist Tanzania. As such, it is an important contribution to Tanzania’s cultural history that complements previous scholarly research.

Uta Reuster-Jahn

Uta Reuster-Jahn, PhD, has been a lecturer in Swahili language and literature at Hamburg University, Germany. Since working in Tanzania in the 1980s, she has been connected to the country. She has widely published on oral literature, popular literature, Bongo Flava music and Urban Youth Language (Lugha ya Mitaani) in Tanzania.

POLICE ADMINISTRATION AND LAW ENFORCEMENT IN TANZANIA: A STRATEGIC TRANSFORMATION PERSPECTIVE. Said Ally Mwema. Rhythm Publishers, Dar es Salaam, 2023. 264 pp. (paperback). ISBN 9789976535419. (Distributed for free to police forces and training institutions in Tanzania and Zanzibar, and to be made available online – details to be announced.)

Once you get this book by the former Inspector General of Police Said Ally Mwema in your hands, you won’t want to put it down. It offers useful suggestions for enhancing the efficiency and professionalism of the police and provides a road map for developing a more responsive, effective, and community-focused police force, covering new technologies, training programmes, and community policing involvement. Its chapters delve into these complexities, examining the effects of globalization on law enforcement and the need for new thinking and new strategies to keep pace with the evolving nature of crime that is at the forefront of policing.

We learn from Mwema’s book that Major S.T. Davies arrived with 31 officers in Lushoto, Tanga, to establish the first police headquarters, which was later shifted to Morogoro in 1921 and then again to Dar es Salaam along Kilwa Road in 1930. We also learn that the first police station in the country was inaugurated at Lupa Gold Mine in Chunya, Mbeya, in 1925. Policing in the country has come a long way since then, but, as this book makes clear, much more remains to be done.

The security of life and property is the bedrock of the social, economic, and political stability of any nation. Governments are saddled with the responsibility of ensuring internal security through established agencies empowered by law. This duty is distilled into standard policing to enforce law and order in the wake of a safe environment. The standard of policing available to a nation determines the level of development of that country. Unfortunately, Tanzania has not always been able to live up to these expectations, even though currently it is undertaking reforms to enhance policing performance.

Part of the problem is that the police must grapple with a myriad of challenges. The police force suffers a deficit of public legitimacy and support; the public does not trust the police because their performance is deemed inadequate. Also, the public regards the character and level of accountability of the police as grossly unsatisfactory. The policemen and women in the country are generally feared but not respected, and they are widely despised for being very brutal when suppressing people who rise to demand political and civic rights. They are notorious for demanding bribes but very casual when it comes to enforcing law and order. People in communities therefore often want to keep their distance from the police.

The writer proposes several strategies to foster effective policing in Tanzania and the modernization of the force. They are built on the assumption that public security and safety are fundamentally rooted in the communities as they are socio-economic and political concerns. Therefore, engaging the public in policing is logical and essential to build mutual trust and empower the citizenry to be informed and competent partners in support of national efforts to ensure public security and safety.

Community policing requires police leaders who are skilled in community engagement. They also need to be strong believers in the rule of law and collaboration with other security agencies. Currently, there is community disillusionment with the traditional, top-down approach in which community policing is implemented within the existing militaristic structure and where political interference, poor leadership, corruption, excessive use of force and torture, and lack of effective oversight and accountability are endemic. A real change in the regulatory and institutional structure is critical, including an improved enabling environment in which community policing and the criminal justice system are better aligned.

There is a need to assess the impact of strategies adopted so that closer alliances between the police and the community reduce citizen fear of crime, improve police-community relations, and facilitate a more effective response to community problems and sharing of information in a timely, accurate and effective manner between the community and the police. Much work is needed to improve the way community policing is currently done in Tanzania to achieve a high level of sustainable trust between the police and the community of stakeholders. A first step must be to transform the Tanzania Police Force into a Police Service.

Mwema discusses all this and more in this engaging and thought-provoking book. Having had the privilege of reading both the English and Swahili versions, I can confidently say that it will be an invaluable resource for all stakeholders, including law enforcement professionals, criminal justice students, and citizens who care about the safety and security of our country. Not least it offers a fresh perspective on the situation that faces policing today and constructive proposals for a much better future, one that matches our President’s own vision and expectations for a thoroughly modern and professional police service.

It will be challenging to fill Said Ally Mwema’s former role, but in writing this book he has proved himself our best guide. There is something in the book for everyone, which is a credit to the author, not only for sharing his experience and insights, but also for showing us how policing in Tanzania can meet the challenges facing it in the 21st century.

Hildebrand Shayo

Dr Hildebrand E. Shayo is a UK-educated scholar with BA (Hons.) MA and PhD in economics; currently employed at Tanzania’s TIB DFI Development Bank, a 100% state-owned development financial institution, as Principal Officer, Agency Funds Solicitation and Administration expert. Dr Shayo has authored three books, produced more than 300 articles, published widely in national and international publications, and contributed to book chapters. Dr Shayo is a board member of the Tanzania Broadcasting Corporation (TBC) and a columnist for the national English newspaper Daily News.

RELIGION, EUGENICS, SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS: AN ETERNAL KNOT. Karim F. Hirji. Daraja Press and Zand Graphics Ltd., Toronto, 2023. 378 pp. (paperback). ISBN: 9781990263224. US $37.00 (e-book US $7.99).

This is another spectacular book, written in Hirji’s small home in Upanga, Dar es Salaam, with the help and support of his wife Farida. It continues his previous book Religion, Politics and Society reviewed in Tanzanian Affairs 135.

The first main section, about eugenics, is particularly interesting, because the topic has almost dropped out of contemporary discourse. Eugenics is a belief that “human populations can be made more healthy, more intelligent and less prone to ‘vice’” by processes of selection. These can be positive, as when “gifted people” are encouraged to marry each other. But very dangerous are those who advocate that people who are not gifted, or have illness or disabilities, should be prevented from marrying, or, taking the argument to its logical conclusion, sterilised or put to death. Such beliefs, based on science which underplays the importance of nurture rather than nature, provided Hitler with arguments to justify the genocide of groups with physical or mental diseases or from the fringes of society. With support from eugenicists in the United States he quickly extended this to the killing of Jews, Communists, other political opponents and people from the Slav countries. More Soviet citizens died than Jews during the Second World War, and nearly 2 million non-Jewish Poles.

Eugenics was invented in England, and widely adopted in the United States. Hirji shows that a remarkably wide range of intellectuals signed up to it – Charles Dickens, George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells, Beatrice and Sidney Webb, D.H. Lawrence, Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, and Bertrand Russell, to take just some, and politicians including Winston Churchill and Neville Chamberlain. In America the ideas were promoted at Harvard University, and eugenics research was sponsored by the Carnegie and Rockefeller Foundations, and was reflected in the thinking of Supreme Court judges such as Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., and Presidents such as Warren G. Harding, William Howard Taft and Theodore Roosevelt. This partly explains why so many Western leaders were slow to appreciate the dangers posed by Hitler and the Nazis in the 1930s.

In our own times, similar views of ethnic or racial superiority have lain behind the policies of authoritarian leaders such as Narendra Modi in India, Jair Bolsenaro in Brazil, and Viktor Orbán in Hungary. Given the inequalities in the present world, and the willingness of authoritarian regimes to demean and persecute minority groups, this is a story that needs to be retold, and Hirji’s 60 pages are as good a start as any.

The section on science is largely philosophical, examining such questions as “Does God exist?”, or what free will means in a world dominated by advertising and social media, and its relationships with morality, or what can be said about consciousness. Hirji is sympathetic to the view that science and religion are different, and often complementary, ways of looking at the world.

The third section, on mathematics, is largely historical. The first numbers were recorded 20,000 years ago. 5,000 years ago, the South American Inca codified their book-keeping into a formal written discipline with symbols and numbers. Pythagoras’ theorem for the sides of a right-angled triangle was discovered independently in tropical Africa, China, Mexico, Iraq, Egypt and India more than 2,500 years ago. The mysterious number called zero came relatively late. It was first used in India about 1,500 years ago, and the even more remarkable one which we call infinity (it is always bigger than anything you have previously thought of) was at first more a theological belief (in the infinite love of God) than a mathematical one.

Many of the pioneering mathematicians were persecuted, especially when they drew conclusions about the stars and the planets which their sponsors did not want to hear – hence Copernicus, Galileo, and Kepler. Newton was a mathematician, a person of the world, and also a devout though unconventional Christian, as were many other leading scientists and mathematicians. In today’s world, mathematics is often misused – not least by internet companies which collect data about their users in order to feed them advertising material, or national security agencies which collect information about those they do not like. Or pharmaceutical, tobacco and petrochemical companies which distort statistics to sell their products.

The book is full of interesting reflections. Religion features in all the chapters, but it plays a relatively subsidiary role in the arguments of this volume. Its treatment is always liberal-minded and sympathetic. The book was written before the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, the rapid development of the climate crisis, and the unexpectedly fast development of artificial intelligence. But where it concentrates, it provides clear and well-written summaries – of the philosophy of science, and the discoveries of numbers from their earliest identification to the non-Euclidean geometries used by Einstein in his theory of relativity. And of the use of genetics and statistics to develop the pseudo-science of eugenics, and the links between US leaders and Hitler that resulted. Anyone who reads this book can expect to make new discoveries.

Andrew Coulson

Andrew Coulson worked in the Planning Unit of the Ministry of Agriculture in Dar es Salaam 1967-1971 and taught agricultural economics at the University of Dar es Salaam 1972-76. His edited book African Socialism in Practice: The Tanzanian Experience was published in 1979. Tanzania: A Political Economy followed in 1982, with a second edition in 2013. His most recent book, with Antony Ellman and Emmanuel Mbiha, is Increasing Production from the Land: A Sourcebook on Agriculture for Teachers and Students in Africa (Muki na Nyota, 2018). He was Chair of the Britain Tanzania Society 2015-18.