by Ben Taylor

When American conservationist Esmond Bradley Martin (1941-2018) was brutally murdered in his home in Lang’ata, Nairobi, on 4th February 2018, the world lost one of its most dedicated and fearless wildlife investigators, known for his meticulously researched reports on illegal trading in rhino horn and elephant ivory.

The East African coast also lost one of its best researchers. He began his career by writing about Malindi and the Lamu archipelago, before moving on to study the dhow trade. Cargoes of the East, written with his wife Chryssee, is now a classic, as is the keenly observed account of his research trips in the mid-1970s, Zanzibar: Tradition and Revolution, still one of the best introductions to the islands.

After an absence of 30 years, Martin returned to Zanzibar in 2006 to attend a conference on dhows and sailing in the Indian Ocean. With characteristic energy and enthusiasm, as well as looking up old friends and making new ones, he also found time to collect material for an article on the local trade in African civet skins.

He’ll be remembered most, though, for his undercover research into the global ivory and rhino horn trades. His tragic murder was widely covered in the international press, along with ample speculation on the reasons for it (a botched robbery? A contract killing?). The case remains unsolved.

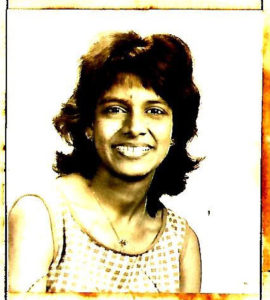

Martin Walsh

Born in Zanzibar, Ophelia Mascarenhas (1938-2017) completed her Cambridge School Certificate in 1953, was accepted at Makerere University College to read for an Honours Degree and graduated from University of London in 1962. She joined her husband Adolfo Mascarenhas at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) where she studied School Librarianship, awarded MLS (1965) and appointed as Librarian at the University of DSM in 1966. Later, Ophelia was the first woman in Tanzania to get a Fulbright Scholarship; and was selected to join a University of her choice, Clark University which had close connections to the University of Dar es Salaam. In 1986 she obtained a PhD in Geography.

Ophelia was a highly respected reference librarian, as well as a researcher/scholar on information and gender studies in her own right. She transformed the East Africana Collection to become the flagship for research and information in East and Central Africa and encouraged students, staff and other researchers to explore relevant information and not be stuck in their disciplinary bias.

Ophelia was promoted through ranks at the UDSM to become the first Tanzanian Professor of Library Studies. She served as Director of the UDSM Library from 1986 to 1991 where she significantly contributed to the improvement of library services in general. In 1995 in recognition of her hard work and dedication, she was declared the best UDSM worker from the University Library. She was not only an administrator but an innovator, pushing for the then new technology CD-ROM with a grant from Carnegie to help researchers and students, and also started an Environmental Data Bank with the support of DANIDA. Her services were widely sought and she served as an advisor to the Irish Embassy for their Development Work in Morogoro Region, advocating for self-reliance and participation. Ophelia was appointed by President Mwinyi to be the Chair of the Tanzania Library Services (TLS) and during her tenure TLS expanded beyond Dar es Salaam into every Region with the mandate that secondary school pupils be given full access. In 1996 she took a sabbatical and moved to Harare, as a Human Resource Director in the Centre for Southern Africa newly established by the Rockefeller Foundation.

Throughout her life, as a teacher in Zanzibar and later librarian/ researcher at UDSM, Ophelia fought all types of discrimination and infringement of the rights of workers, women, rights of people to information on resources, including land, and contributed to the advancement of women/gender studies. She and Marjorie Mbilinyi prepared

Women and Development in Tanzania: An Annotated Bibliography for UNECA (Addis Ababa, 1980), and a more detailed analysis of women’s resistances and struggles in 1983 with additional annotations, Women in Tanzania (Uppsala, Scandinavian Institute of African Studies). The Bibliography went through nine editions. As the value of her work gained ground beyond Tanzania there was no lack of support from international agencies (SIDA, NORAD, DANIDA, UNU, the Ford Foundation etc). Ophelia was also a resource person for numerous local institutions and an active participant in public fora organised by REPOA, Policy Forum, ESRF, Twaweza and TGNP Mtandao. Ophelia prepared Gender Profile of Tanzania: Enhancing Gender Equity for TGNP and SIDA in 2007 and the Gender Barometer for Tanzania (TGNP) in 2016.

After retirement, Ophelia became the Coordinator and researcher of a large four country study on ICTs in Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda and Tanzania. This was followed by a related study supported by DFID through the Tanzanian Commission of Science & Technology (COSTECH), The Economic Impact of Telecommunications on Rural Livelihoods and Poverty Reduction in Tanzania which documented how ICT increased the gender and income gap between rich and poor. In her presentation at the Harvard Forum in 2009 she remarked that the use of mobiles had increased from to 25%, but warned that mobiles would siphon off money from the poor without support and training. She got the assistance of Airtel to train 100 micro small operators to keep accounts, use mobiles for ideas communication and markets. Following the launch in Dar es Salaam of ICT Pathways To Poverty Reduction, Ophelia was surrounded by girls from secondary and post-secondary schools, full of admiration, pride and hope that girls and women had an important contribution in bringing change.

Marjorie Mbilinyi in consultation with family members

Veteran free-thinking politician, Kingunge Ngombale Mwiru (1930-2018), was both a patriarch and a rebel. Hi rebellious streak was at its most evident in his 2015 decision to join Edward Lowassa in defecting from CCM to Chadema, despite holding very different views from Lowassa (and Chadema) on economic matters. He stuck with this change after his preferred candidate lost the 2015 presidential election, even while many of the others who shifted party at the same time returned to the ruling party fold.

But Kingunge’s 2015 act of rebellion was certainly not his first. He was no stranger to controversy, and loved political and philosophical debate. In the 1970s, as serving government representative he refused to support a government motion in parliament. The government lost the motion and he was fired. He found himself in disagreement – sometimes public – with Mwl. Nyerere on numerous other occasions when his Marxist worldview meant he tried to push the party and country further to the left than Nyerere was willing to do. At a time when Nyerere was held in awe by many around him, when the accepted practice was to clap hands and nod approvingly at whatever the leader said, Kingunge would speak up and present an alternative view.

As a teenager in the mid-1950s, Kingunge joined the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) and worked in various capacities including secretary-general of the party’s youth league. In the 1960s, he went for university education to Liberia and Senegal, and spent some time at the Sorbonne in France. In the 1970s and 1980s, he was the chief ideologue of TANU and CCM, having taught at the party’s ideological institute at Kivukoni, Dar es Salaam. He became a key interpreter of the party’s ideology of Socialism and Self-Reliance, and was among the key figures on the process of joining TANU and the Afro Shiraz Party (ASP) of Zanzibar to found Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) in 1977. At various times he held ministerial posts, served as an MP and as Regional Commissioner in four different regions, and as secretary of the CCM National Executive Committee.

“His passing marks the end of an era,” said fellow political veteran, Jenerali Ulimwengu. “He is probably the last of the young people who joined the ranks of independence campaigners and stayed on to serve his party, and country. His was an age of the politics of conviction and commitment; he has checked out in the age of the politics of expediency and convenience.”

“Kigunge has contributed a lot for this nation,” said President Magufuli in a statement. “We will never forget what he did for this country. We will remember his good deeds and most specifically his fight for the interests of the nation, particularly in maintaining peace and unity,” he said.

Socialite, model and “video queen”, Agnes “Masogange” Gerald (1989-2017), was a regular on the front pages of Tanzania’s celebrity obsessed Udaku tabloid newspapers. She made her name as an actress in Tanzanian music videos, and indeed quite literally took her stage name after featuring in one such video by Belle 9, called “Masogange”.

In one sense, Masogange was a master of suggestion – hinting at affairs, pregnancies and more on her social media profiles. Editors loved it – this was exactly the kind of gossip and scandal that sold their papers. In another sense, she was far from subtle: a google search for her image shows a wide selection of photos drawing attention to one thing in particular – her curvaceous behind. This too sold papers. Her profile on Instagram, a photo-sharing social media platform read “I got ass, I’m beautiful, I know how to make money.”

She attracted headlines too for her alleged drug use. Two weeks prior to her death, she was sentenced to a fine of TSh 1.5m ($700) or a two-year jail term, having been found guilty of using heroin. She was among the first of the high-profile targets of the efforts of Dar es Salaam Regional Commissioner, Paul Makonda, to clamp down on drug problems. This was not her first drug-related case: in 2013 she had been arrested at a South African airport in possession of suspicious chemicals.

Masogange died at the young age of 28, while receiving treatment for pneumonia at hospital in Dar es Salaam.