(Reproduced from a Report of an International Study Team on the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Dar es Salaam, May, 1979)

The industrial development of Tanzania falls into two broad and overlapping stages, the development of consumer-related production with a large element of import substitution and the establishment of extractive and capital goods industries based largely on domestic reserves of raw materials. The first of these types of development was characteristic of the early years after Independence and particularly the years following the Arusha Declaration of January 1 1967, with its emphasis on self-reliance.

Development for the consumer market will continue in response to population growth and rising expectations, but according to present plans will gradually yield in emphasis to the building up of basic and capital goods industries relying on the local mining and extraction of raw materials, particularly iron and steel. Industries of this kind have already been established on the basis of imported materials, notably the steel rolling mill at Tanga, the fertiliser factory also at Tanga and the oil refinery at Dar es Salaam.

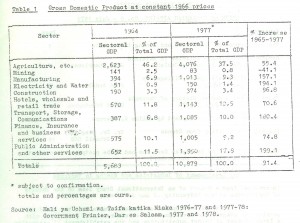

The growth of industrial activity during the years from 1964, the beginning of the First Five Year Plan, to 1977 can clearly be seen from the published figures of the Gross Domestic Product as set out in Table 1. The pattern of the monetary economy is there seen to have shifted markedly away from agriculture towards industry, water and electricity, building, transport and communications; in other words, towards the industrial sector of the economy.

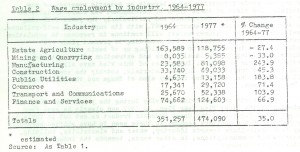

While the contribution of agriculture has risen by 55%, its relative contribution has fallen from 46% to 38%. Meantime, manufacturing industry has registered a growth of 157% and an advance in relative importance from 7% (3-4% at Independence in 1961) to over 9%. Still greater progress has been made by water and electricity (194%) and by transport and communications (180%), that is, by economic infrastructure. The recession in mining is referred to later in this chapter. Another indicator of the shift towards industry, public utilities, communications, etc., is provided by the employment figures given in Table 2.

Table 1 - Gross Domestic Product at constant 1966 prices

Source: Hali ya Uchumi wa Tajfa katika Miaka 1976-77 and 1977-78: Government Printer, Dar es Salaam, 1977 and 1978.

Table 2 Wage employment by industry 1964-1977

By 1976, the metal fabrication industries already accounted in money terms for nearly 10% of industrial production, while consumer goods occupied 65% of the total. Between 1965 and 1976 the consumption of electricity by industry rose from 36.0 million kilowatt hours to 185.3 million, a more than five-fold increase, while employment rose two and a half times, from 28,100 to 74,200. Meantime, the production of portland cement, begun near Dar es Salaam in 1966, rose from 50,000 tonnes in that year to 296,000 tonnes in 1974, though it fell slightly on account of labour problems to 244,000 tonnes in 1976. Urban water supplies increased from 12,800 million litres in 1963-64 to 61,000 million litres in 1976-77. At Independence in 1961 there were some 500 km. of macadamised trunk roads; by 1977 there were 2,625 km. (1)

More than most other African countries, Tanzania has from the first been notable for the thoroughness of its economic planning . At present such planning is carried cut within three time perspectives, namely, a 20 year plan setting out broad objectives and desired trends for the main features of the economy; a five year plan detailing the strategy for the ensuing five years; and an annual plan, which incorporates any necessary modifications to the five year strategy enforced by world circumstances, the accident of weather, planning delays and other influences….

Long-term planning of the economy for the period 1975-95 is based on consideration of the following main objectives:

(1) modification of the structure of the industrial economy in recognition of the need –

(a) to establish export industries in order to attract foreign exchange and to assist agriculture in increasing foreign exchange reserves;

(b) to establish industries producing for domestic consumption and development;

(c) to establish industries for the production of spares, fittings and machine parts to enlarge the national basis of self-reliance and to extend the domestic market for manufactured iron and steel with a view to facilitating the establishment of a metallurgical industry;

(d) to establish basic industries relying on domestic sources of raw materials, including iron and steel, coal, chemicals and building materials;

(e) to set up small scale industries based on simple technology and located in villages, where the greater part of the population live, with the object of promoting rural development;

(2) increasing industrial production and productivity;

(3) increasing employment and extending opportunities for education, training and the increase of skills;

(4) ensuring a fair distribution of industries by Region ; and

(5) providing and extending facilities for research, advisory services and technological information for the benefit of industry.

The intention of the long-term plan is to increase the contribution of manufacturing industry to the gross domestic product from nearly 10% in 1977 to around 20% by 1995; to increase the contribution of metal fabrication to industrial output from 10% to 30% and to reduce the contribution of consumer goods to the total from 65% to 40%. The general burden of the plan is, therefore, to change the balance of the economy decisively in favour of the extractive and capital goods industries, not at the expense of consumer goods, but in terms of relative growth. The establishment of industries for the manufacture of iron and steel is to have top priority in order to supply the needs of the metal fabrication and construction industries. At the same time the cement, glass products and wood products industries – all using local raw materials – will be increased to give added support to the construction industry, while factories producing chemicals, fertilisers, paper and printing machinery are to be developed.

… Between 1980 and 1985 top priority will be given to the development of the following basic industries, viz., iron and ferrous products, cotton, leather and sisal, chemicals, various foodstuffs, paper and wood, and non-ferrous products (e.g., cement and building materials). Meanwhile, the domestic market will, it is hoped, have been developed sufficiently to justify these activities. A start with the iron and steel, chemicals and paper industries already appears in the Third Five Year Plan (1976-81).

… Some 194 million shillings are set aside in the 1978-79 capital budget for roads, bridges, airports and other related works; 184 million shillings for various water development schemes; 446 million shillings for various electricity generating and distribution projects, notably, Phase 2 of the Kidatu hydroelectric scheme (229 million shillings); 140 million shillings for developments in the telephone and telex services; 586 million shillings for the improvement of the railway system in Central and Northern Tanzania; and a variety of Regional projects. (2)

Crucial to the development of industry in Tanzania is the expansion of the electric power supply. In 1975 the total capacity of the power supply system was 150 megawatts, of which 86% was sold in the coastal area and around Arusha and Moshi. In 1976 the first Phese of the Kidatu hydroelectric power scheme on the Great Ruaha River came into operation with a further 100 megawatts, a system that has now been connected by land line to Dar es Salaam. Phase 2 of the Kidatu scheme will shortly be completed, with a further 100 megawatts.

Meantime, considerable preparatory work has been carried out in Conjunction with NORAD (Norway) on the Stieglers Gorge project on the Rufiji River. (3) Reports have been submitted, not only on the construct1nn of the dam, but also on the use of power from Stieglers Gorge for the manufacture of iron and steel from the Liganga deposits of iron ore and the establishment of power-using industries based an local raw materials. Tha Stieglers Gorge project is therefore more than a hydroelectric power scheme, it is a plan for an industrial complex of considerable potential size and importance. The dimensions of this undertaking may be judged from the expectation of a power output of 600 megawatts, four times the total output in the whole of Tanzania in 1975. Further potential capacity lies in the Kiwira River scheme in Mbeya Region, with a maximum possibility of 233 megawatts, of which 14 megawatts are expected to be produced during the Third Five Year Plan; and in the Rusumo scheme, now under investigation, with a potential of 90 megawatts. A start will also be made during the Third Plan with a coal-fired thermal station based on local mines in view of the rising cost of oil.

As already indicated, long-term planning relies on the development of local resources of raw materials, particularly iron and coal. It remains, therefore, to describe those resources and the prospects of their gainful exploitation.

At Independence diamond mining was much the most extensive and lucrative form of exploitation of Tanzania’s natural resources, with gold following second in importance, yet for many years before that other minerals were known to exist in commercially significant quantities. Since virtually the entire mineral output was exported, it formed a valuable source of foreign exchange, but did virtually nothing to promote mineral-based industries within Tanzania. During the First Five Year Plan (1964-69), small quantities of coal, tin, mica, magnesite, tungsten, lime, salt, gemstones, glass-sand, kaolin and gypsum were produced; gypsum and lime were mined largely for internal consumption and salt was exported after meeting the domestic demand. Diamonds and gold, however, accounted for about 90% of production.

In 1966, the Geita and Kiabakari gold mines closed and in 1970 the Buhemba mine. Thereafter production remained small, but plans are afoot to open further mines during the Third Five Year Plan period at Lupo in Chunya District, in Geita District and elsewhere, which are expected to achieve an appreciable output.

Diamonds have for long been the most valuable mineral in Tanzania. In 1968, diamonds to the value of 164 million shillings were mined and exported. But the mines were becoming exhausted and in 1968 the remaining life expectancy was only ten years. In the event, however, it has proved worthwhile to continue mining, despite falling output, in view of rising world prices. While, however, the continuing diamond output was a useful asset in world markets, attention has increasingly turned to the exploitation of the country’s iron and coal resources and the importance of these minerals as a foundation for local industry.

Although coal has long been mined at Ilima colliery on a very small scale for a local market, there are known to be extensive reserves of bituminous coal at Songwe/Kiwira, in which Ilima is situated at Mchuchuma/Yateweka. Chinese experts are studying the possibility of using coal from the Songwe/Kiwira reserves for the smelting of iron from Chunya; in addition its use for coal-burning thermal generators, the production of tar for road making and the production of a simple ammonia fertiliser have been considered. The use of the Mchuchuma/Kateweka reserves for smelting the Liganga titaniferous ores has presented difficulties and is still under investigation.

Exploration has shown that iron ore deposits in Chunya District are extensive and capable of producing 250,000 tonnes of iron per annum. Reports have also revealed the presence of extensive ore deposits at Liganga in Njombe District with an annual potential of 500,000 tonnes. The Liganga ores, which have a 49% ferrous content, contain 13% of titanium dioxide and some associated vanadium. A West German team of experts is making a technical and economic study of the possibility of separating the vanadium and titanium. Meanwhile, a feasibility study by NORAD (Norwegian Government) of the use of power from the proposed Stieglers Gorge hydroelectric scheme for the manufacture of iron and steel from the Liganga deposits has been completed.

The prospect for mining operations both of coal and of iron ore depend not only on the completion of the technical and economic studies now proceeding, but also on the construction of the necessary infrastructure, notably road and railway links, the necessary outlets for the products in local industries and abroad. This is a complex operation and the ramifications of it suggest that it may yet be some years before large scale mining operations can begin. Owing to the technical problems still to be surmounted and the work on associated industries and services still to be put in hand, it is too soon to put a firm date on the onset of extensive mining operations. Nevertheless; the studies already made and the information gained suggest that the exploitation of Tanzania’s iron ore reserves most probably will begin within the coming decade.

Although the mining of Tanzania’s iron ore reserves is dimensionally and economically much the most significant development to be expected with reasonable certainty in the near future, considerable effort has also been expended on the investigation and development of other mineral resources. A search for exploitable oil reserves in the coastal sedimentary belt, started during the Second Five Year Plan, is continuing in the Southern Mainland, the Ruvu valley, south-east of Zanzibar and offshore. In the course of this search, natural gas was found at Songo Songo in Kilwa District and studies are now proceeding on the feasibility of its use in the manufacture of chemicals, especially ammonia.

Meantime, the steep rise in price of phosphates imported from the Middle East for the fertiliser factory at Tanga has precipitated research into the possibility of using phosphates mined at Minjingu, of which there is said to be a 10-20 year supply. Studies are also being made of the direct use of this mineral as a fertiliser. This project has, however, encountered financial problems.

Salt is a universal requirement for domestic use and the State Mining Corporation (STAMICC) has been preparing for the mining of salt to help to meet this demand and for export. Meantime, studies of the mining of gypsum are proceeding at Mandawa in Kilwa District to supplement the gypsum mined at Mkomazi in North-East Tanzania as a source of supply for the cement factory at Wazo Hill, near Dar es Salaam. At Lake Natron there are considerable deposits of soda ash and studies have been made of the refining and extraction of potassium and sodium chloride and of the technical, economic and transport problems involved.

The Third Five Year Plan includes plans for mining operations at Lake Natron on a small scale. Reserves of magnesite at Chambogo in the Pangani Valley are being investigated with the help of West German support. Other minerals under investigation are tin and tungsten in te Karagwe area, including the possibility of reopening the Kyerwa mine closed in 1971; asbestos, hitherto recovered in small quantities at Ikorongo in Serengeti District and elsewhere; copper, cobalt and nickel in the Piti River south of Tabora; and a number of rare earths and natural abrasives. Kaolin is produced in the Pugu Hills near Dar es Salaam and used for ceramics and potentially for paper making, with glass sand as a by-product. Finally, there has for some years been a successful industry in gemstones including the attractive green ‘Tanzanite’ which in 1976 contributed a useful 3 million shillings to the country’s foreign exchange reserves.

Mining operations in Tanzania have reached a transitional stage. Hitherto, diamond mining has stood out as much the most extensive and lucrative operation, but the ascendancy of the diamond is drawing to an end. Most other mining operations are at present limited, though prospecting and economic assessment is proceeding on a considerable scale. Among the known resources, those of iron and coal are extensive and a substantial home-based metallurgical industry is in prospect in the near future. If this branch of industry is successfully established, it will have a profound influence on the location and character of industry, on movements of population and on the pattern of Regional growth. Although these results are now fairly well assured, it is still not possible to attach a time scale to the industrial revolution that iron and steel making will induce in Tanzania. (4)

This account of the prospects for the economy would be incomplete without passing reference to the growth of small industries under the general superintendence of the Small Industries Development Organisation (SIDO). The long-term aim of this body is to promote small industries in the form of production cooperatives, particular]y in the villages, thereby not only advancing rural prosperity, but also decentralising the production of such consumer goods, components, etc., as can be produced economically on this basis. Small industries will be labour intensive and capital extensive and will therefore in many cases call for adaptation of methods of production and a resort to simple productive procedures. Such adaptations will offer a considerable challenge to engineers, involving not simply a reversion to historic semi-manual methods of production, but a modification of modern technology with the greatest economy in capital investment and a maximum use of human and other local resources. The importance attached to this development by the Government can be seen from the allocation of T shs. 117,241,000 to SIDO projects in the single year 1978-79.

References

(1) Sources of statistics: Bali ya Uchumi wa Taifa katika Mwaka 1977-78 ; Bank of Tanzania Economic Bulletin, Vol.IX No.3, Dec. 1977 ; Taarifa ya Hali ya Uchukuzi na Mawasiliano Nchini; Government Printer, Dar es Salaam. Mpango wa Tatu wa Maendeleo ya Miaka Mitano ya Kiuchumi na Jamii, 1 Julai 1976-30 Juni 1981 : Sehemu ya Kwanza- Shabaha na Maelekezo: Government Printer, Dar es Salaam.

(2) Mpango wa Maendeleo wa Mwaka 1978-79: Government Printer, Dares es Salaam. It is, unhappily, more than probable that substantial parts of this programme have fallen victim to the Uganda War and will have to be postponed.

(3) Details are taken from Norges Samarbeid med Utviklingslandene, 1977: NORAD, Oslo, 1978.

(4) The facts in this section on mining operations are taken from the following sources: Tanzania Second Five Year Plan for Economic and Social Development, Vol.1: General Analysis, Chap. 5; Mpango wa Tatu wa Maendeleo ya Kiuchumi na Jamii, Kitabu cha Kwanza, Shabaha na Maelekezo, na Kitabu cha Pili, Miradi: both Government Printer, Dar es Salaam. Mpango wa Maendeleo wa Mwaka 1976-77, 1977-78 and 1978-79; Government Printer, Dar es Salaam, 1976, 1977 and 1978 respectively. Hali ya Uchumi ya Taifa katika Mwaka 1974-75, 1975-76, 1976-77 and 1977-78: Government Printer, Dar es Salaam, 1975, 1976, 1977 and 1978 respectively.