by Martin Walsh

IN THE NAME OF THE PRESIDENT: MEMOIRS OF A JAILED JOURNALIST. Erick Kabendera. Staging Post (Jacana Media), Johannesburg, 2024. 354 pp. ISBN 9781991220929 (paperback). £18.95; also available as a Kindle Edition.

In 2019, Erick Kabendera was one of the most prominent victims of President John Magufuli’s crackdown on critics. As one of Tanzania’s most respected investigative journalists, his work had appeared in leading national and international newspapers – including The Economist and The Guardian. Under President Magufuli he served seven months in prison on unconvincing charges, following his investigations into several matters that caused or promised considerable embarrassment to the President – his state of health, his family relationships and multiple cases of apparent corruption and mismanagement.

In this book, Kabendera tells his story. It has three interwoven strands: Kabendera’s personal experience,

Magufuli and his presidency, and Tanzania’s wider history. He tells the first of these in straightforward terms, never over-dramatising or self-pitying, though the experience was clearly harrowing. The dire state of Tanzania’s police service and prison estate and the extent of political manipulation of the police, justice system, immigration service and tax authorities are laid bare.

On the country’s wider history, Kabendera explores the background to President Magufuli’s rule, looking back as far as President Nyerere’s heavy-handed approach to critics, but devoting most attention to the corruption that was seen to thrive under President Kikwete and the efforts of CCM big-wigs to ensure that Edward Lowassa did not become the party’s presidential candidate in 2015. We get a deep dive into the IPTL corruption scandal and its consequences at the highest political levels. And the manoeuvring to push John Magufuli’s candidacy, despite the reservations of those who knew him best, is presented in some detail.

The book makes a strong implicit case that a Magufuli-like figure was bound to emerge at some point: the history of authoritarian tendencies, lack of strong democratic norms, and highly centralised power structure combined to create the opportunity for a strong-man to take charge. The particular dynamics of CCM in the first half of the 2010s then thrust Magufuli forward into the role, which he was only too happy to fill.

Kabendera does not pull his punches. The charges he lays at the President’s door are wide-ranging and serious in the extreme. He accuses Magufuli of incompetence and mismanagement, nepotism and extensive corruption in his role as President. He accuses him of extreme misogyny and spousal abuse – and hints at more – in his personal life. He avers that the late President suffered not just from serious heart disease, but also from schizophrenia and extreme superstition, which he claims at one time prompted “a fear of being ensnared by ghosts purportedly sent by his predecessor, Jakaya Kikwete and the CCM Secretary General Abdulrahman Kinana.”

Shockingly, Kabendera alleges that Magufuli personally committed murder, shooting Ben Saanane, a senior opposition party figure, in the grounds of State House, in retribution for having publicly cast doubt on the President’s academic qualifications. He argues that the President’s belligerent attitude towards his perceived opponents fostered a determination among acolytes to curry favour by anticipating his desires and acting even without receiving directions. There is a suggestion that this lay behind the attempted assassination of opposition leader Tundu Lissu.

Putting all this and more together, Kabendera paints a picture for us of an intensely paranoid, thin-skinned and venal President, who lacked the political skill (and inclination) to play the game by democratic means, but who resorted instead to authoritarianism, manipulation and brutality. In this view, Tanzania had a lucky escape in the manner of the President’s premature exit from the stage, which Kabendera unambiguously attributes to Covid-19 and pre-existing heart problems.

More worryingly, however, the conditions that gave rise to President Magufuli are said to remain largely unchanged. The manner in which an incompetent leader – in Kabendera’s description – was able to seize control of key organs of the state and manipulate them to his own ends should be a major concern.

Before concluding, it would be remiss not to mention some of the book’s evident shortcomings. First, there are extensive inconsistencies and factual inaccuracies. Some dates given in the author’s personal story are incorrect, as is the year in which Prime Minister Edward Sokoine died in an apparent car crash. The sequence of events when opposition leader Zitto Kabwe paid a visit to the Director of Intelligence Services has been corrected by Kabwe himself. And there are several misspelled names. These may be little more than typos and proof-reading errors, but they do not inspire confidence.

Second, given the seriousness of the accusations laid out in the book, the minimal supporting evidence presented in some cases is problematic. Protection of sources is a key journalistic imperative, but so too is the need to demonstrate the credibility of such explosive claims. It will be much easier for Magufuli’s supporters to challenge Kabendera’s account than it might have been otherwise.

Third, the author’s writing style often gets in the way of the narrative. A tendency to jump around in the timeline and to omit important details until a story is well-underway left this reader repeatedly flicking back-and-forth through the pages to look for something that had been missed, and several times unable to work out what was actually being said.

And lastly, it is odd that Kabendera did not engage at any length with the incontestable fact that Magufuli remained – and remains – popular with many Tanzanians. This is an important element of the Magufuli story for how it enabled his excesses, for what it says about the state of the country’s democracy, and for how it emboldened (and continues to embolden) his followers. For many in CCM, Magufuli still stands as a model to be emulated.

That said, this book will be difficult to ignore. It may not be perfect, but it is essential reading for anyone with more than a passing interest in Tanzania’s recent history and near future, and the ways in which these are being contested. Under the circumstances, Kabendera’s courage and commitment to telling the truth as he sees it is admirable. It will be interesting to see how the debate over Magufuli’s legacy develops, and whether Kabendera’s warnings are borne out or heeded.

Ben Taylor

Ben Taylor is the Editor of Tanzanian Affairs.

THE OVERHEAD LOCKER: TALES OF TRAVEL, TANZANIA AND TRYING TO KEEP IT TOGETHER. Phil Double. Independently published, 2025.158 pp. ISBN 9798314381182 (paperback) £4.99; also available as a Kindle Edition.

In this book, Phil Double covers two themes – he talks about a family holiday to Tanzania, and the account is overlaid by his struggles with anxiety which affect many of his actions.

He starts the book by discussing in detail his descent into anxiety, over nearly a decade – how it started, how he was unaware of what was happening to him and wondered why he suddenly was unable to eat and was tired all the time, how he sought help and how finally he developed some coping strategies which began to help him with situations such as those he encountered on his monthlong visit to Tanzania. Although he found being with people difficult, he was determined not to hide away, and this was one of the reasons he decided that the family must go to Tanzania.

Double was born in Tanzania, of missionary parents, in a remote village near Singida. He is also married to a Tanzanian, and since leaving as a child, he has visited Tanzania on other occasions. Although familiar with all matters Tanzanian, he found even planning the journey triggered feelings of anxiety.

However, the family – his wife, three children and his mother – made it safely to Tanzania, after some anxious moments on the journey, and immediately went to stay with family in a village on the slopes of Mt Meru. There are some vivid descriptions of village life and Double understands that he is able to find peace in adjusting to the very different way of life, new routines and a slower pace, making the most of each day.

He describes in detail how people in Tanzania access water in their homes, and how difficult it is for many people throughout the country, for a variety of reasons. The family embark on a project to improve the water system in this village, by repairing a tank higher up the mountain. Double hikes up with his father-in-law, through Maasai villages, to investigate the source of the problem, and he is able to gain an understanding of the water issues faced by several communities and individual households. Through the charity he works for, he can donate funds to this project. He is particularly struck by seeing small children struggling to carry heavy water containers to their homes, and is relieved that they will now have extra time and energy to spend on more profitable pursuits as a result of the improvement of the water system.

There are other trips – one to nearby Moshi where his parents worked, a week in Dar es Salaam in a hotel to spend time with other family members and his wife’s friends, and of course, a safari, to Tarangire, where they see all the necessary wildlife. Despite his anxiety, particularly when they have to make journeys, Double enjoys much of their visit. He ponders on the connectedness he feels spending time with his wife’s family, sharing meals, getting to know the children, the older people, and how this turns out to be one of the best ways to counterbalance his anxiety. But he also encounters negative aspects, lamenting the amount of rubbish in the sea along the beach where they are staying, and an example of corruption at the airport – this fills him with frustration as he wonders what new visitors to the country would make of such a blatant display of dishonesty, and he worries that it would influence their view of the country as a whole.

There are many descriptions and incidents in this book that will conjure up familiar images to those who live in Tanzania or those who, like me, have spent time there in the past – the airports, road travel, Dar es Salaam streets clogged with traffic, rural villages with their stunning greenery and busy lives. Plagued as Double is with anxiety, he is brave to have embarked on this journey, although much of it was facilitated by family members, and he comments at the end ‘You can’t reach the end if you never take a step’.

Kate Forrester

Kate lived in Tanzania for 15 years, working as a freelance consultant chiefly in social development, and carrying out research assignments throughout the country. She now lives in Dorchester, where she is active in community and environmental work.

A TRAINING SCHOOL FOR ELEPHANTS. Sophy Roberts. Doubleday, London, 2025. 432 pp. ISBN 9780857528377 (hardback) £22.00; ISBN 9781473597471 (eBook) £9.99.

At its simplest level this is a tale of four Indian elephants (two female and two male) acquired in Pune (Poona), crammed into the hold of a ship in Bombay and shipped to Zanzibar via Aden. These four animals were craned into the water in Msasani Bay, adjacent to the future colonial capital of Dar es Salaam, and swam to shore making East African landfall for the first time. Seven weeks after leaving Pune, on 2 July 1879, the animals and their Indian mahouts, set off in a caravan towards the interior.

Who triggered this operation and for what reason? Leopold II of Belgium, who had in 1865 personally acquired the space of what is now roughly the Democratic Republic of Congo, was the primary instigator. But the fact that he was purchasing and moving these animals through areas of British direct and indirect control, stirred wider official and unofficial interest. Operational leadership was entrusted to an Irishman, Friederich Falkner Carter, who had the advantages of marine logistical experience, as well as a fluency in Arabic acquired during long-term residence in Basrah at the head of the Persian Gulf. He also had a background in trading Mesopotamian fauna into a European market. The overall goal, it could be argued, was to create an equivalent of the Pune elephant breeding centre in an African space utilising African elephants. Those trained elephants would then be used in a variety of commercial contexts, in many cases replacing the role of African labourers.

The expedition absorbed the death of their senior male elephant near Mpwapwa, probably through the strain of overloading the animal. It was at this stage they were joined by a secondary Belgian caravan, adding some confusion as to who was in overall control. Within several days of leaving Mpwapwa, traversing the area of Gogo control, the second male elephant died. After ostentatiously parading through the Nyamwezi centre of Tabora, the caravan angled in a southward direction to Karema on the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika. Within sight of that destination the third (female) elephant died of infections. Stranded in Karema, with one elephant, and starved of reserves, Carter eventually made the decision to return to the coast in order to rejuvenate his mission. Shortly after his departure in June 1880, he was inadvertently caught up in a local African conflict and lost his life; the last remaining elephant in Karema died shortly afterwards.

A unique African elephant training school in the northeast Congo did eventually come into existence some two decades after Carter’s death; its last habituated graduate died in 2010. The book has minimal detail on the initial training structure and mechanics of that later enterprise.

The author, who would see herself as a travel journalist with a sense of history, alternates chapters of the historical journey with her own quest for background in archives and on the ground in Tanzania. She occasionally hints at the wider global story of elephant exploitation in a European and North American context. She briefly mentions the aborted attempt to electrocute an elephant (‘Jumbo II’) in Buffalo NY in 1901 yet fails to mention the more successful public execution of another elephant (‘Topsy’) at Coney Island in 1903 by a combination of electrocution, strangulation and poisoning.

The initial hurried quest by King Leopold for elephants in Europe namechecks the Hagenbeck Zoo in Hamburg but the author makes no further mention of Carl Hagenbeck, arguably the greatest exotic animal entrepreneur of the period before the First World War, a merchant with a preference for female elephants from Ceylon. Several decades later, after Germany had acquired the colonial territory in which our story takes place, the metropolitan German government approved a budget to allow several German contractors to again test the idea of animal transport (not elephants), this time in the south of the East African colony. It was an exercise that produced no practicable results.

Lorne Larsen

Lorne Larson was one of the first doctoral graduates in history from the University of Dar es Salaam. He has taught East African history in Tanzania and Nigeria. He specialises in the German colonial period and is most interested in the history of southern Tanzania.

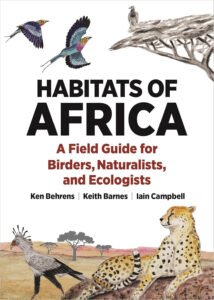

HABITATS OF AFRICA: A FIELD GUIDE FOR BIRDERS, NATURALISTS, AND ECOLOGISTS. Ken Behrens, Keith Barnes, and Iain Campbell. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2025. 448 pp. ISBN 9780691244761 (paperback) £30.00; ISBN 9780691244778 (e-book) £30.00.

Let me review this book from the eyes of a birder widely travelling in Tanzania with a general interest in nature.

Why should we study habitats when the target of most visitors will be birds and mammals? Well, first of all you will discover in this book that Tanzania is home to many different habitats, far more than a first-time visitor will imagine to see. Even on the most classical Northern Tanzania safari tour from Arusha to Ngorongoro and Serengeti you will pass through many different habitats holding their special birds and mammals’ assemblages. Now with just a little bit of preparation (and the book is really very easy to use) you will recognise the Tropical Montane Cultivations around Arusha followed by the Northern Dry Thorn Savanna (Maasai Steppe) when driving to the Rift and arriving either at Lake Manyara or Lake Natron with its salt pans. Climbing the road to Ngorongoro Crater you will pass through the most beautiful Moist Montane Forest with its extraordinary and specific avifauna. When descending on the other side of Ngorongoro you will first enter a very dry area in its rain shadow called Afrotropical Grassland. At this very place you will encounter the millions of wildebeest calving around February when the grass is green, before leaving in March, April to the northwest into the Moist Mixed Savanna called here Serengeti.

Maybe next time you will do the Southern Circuit with a whole different set of habitats, leaving Dar Es Salaam surrounded by East Coast Forest Matrix but soon entering a mosaic of Afrotropical Grassland and a different forest type, the Miombo holding a very different avifauna and mammals difficult to find in other habitats like the African painted dog or greater kudu.

But how easy is it to recognise these different habitats? Two main criteria were used by the authors: their visual distinctiveness with species of vegetation present, e.g. grass versus

trees, that even the most narrow-sighted birder or first-time safari visitor will recognise, and their assemblage of wildlife, primarily mammals and birds.

To get the maximum information out of the book, you only have to read the very short introduction to the main text (11 pages) which includes nice and easy to understand climate descriptions and graphs. Every single habitat is introduced by a map, a climate diagram, and a beautiful black-and-white illustration showing the vegetation and including a human for scale. The habitat is then described in a way that everybody, birder or naturalist and even the novice safari tourist will understand, including numerous very high-quality photographs of the habitat, mammals and birds present and characteristics of the place with a special section explaining why these species of mammals and birds are present. Not to forget the numerous sidebars presenting great information about various topics.

But why is this book so interesting for birders? Well, with more than 1,000 different bird species present in Tanzania, it is essential to know the habitat of the different species. Let me explain with a specialised raptor, the Eastern chanting-goshawk (Melierax poliopterus), often confused with the Dark chanting-goshawk (M. metabates). Looking in your brand-new bird guide and studying the tiny maps you will get an erroneous picture of the distribution of the Eastern chanting-goshawk in Tanzania, although an almost perfect distribution map can be found on the Tanzania Bird Atlas website (http://tanzaniabirdatlas. net/start.htm). But as an owner of Habitats of Africa you can simply look at either page 37 in the East Africa chapter or at page 227 in the Savannas chapter, and knowing that the Eastern chanting-goshawk is a Northern Dry Thorn Savanna bird, you will have a perfect map of its distribution in Tanzania. The habitat as defined by the authors is clearly working!

And this is true for many bird species in Tanzania, especially in the very difficult families with tens of closely related species like sunbirds and cisticolas. Without knowing their habitat, identification, especially when they’re not singing, is an almost impossible task.

Thus this book is perfect for planning your trip, learning much more than you will ever get out of an ordinary field guide, putting your observations in a broader ecological context. By the sheer fact that you will start to understand African biogeography in relation to birds and mammals, your trip will be even more fun.

What else makes this book so appealing? A wealth of information not readily available elsewhere, written for birders and naturalists, explained by first class diagrams and maps and filled with hundreds of excellent photographs. So, from my point of view as a keen birder interested both in African birds and mammals, this is essential guide to prepare a trip and to understand distribution of the avifauna of Africa. It is even more useful with its complementary information about a topic not readily available to birders and others until now. Everybody interested in Tanzanian nature needs this book!

Tom Conzemius

Tom Conzemius is a veterinarian by profession and birder by passion, living in Luxembourg. When he first visited Tanzania back in 2005, he found his Garden of Eden. Since then, he has returned many times visiting the different regions and national parks. He’s especially interested in raptors and for many years has conducted a raptor road count on each trip, an activity which is both enjoyable and may one day be useful as a reference.