by Martin Walsh

SWAHILI SOCIAL LANDSCAPES: MATERIAL EXPRESSIONS OF IDENTITY, AGENCY, AND LABOUR IN ZANZIBAR, 1000-1400 CE (STUDIES IN GLOBAL ARCHAEOLOGY 26). Henriette Rødland. Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University, Sweden, 2021. xii + 321 pp. (paperback and e-book). ISBN 978-91-506-2896-8 (print). Print copies available from online booksellers: free to download at http://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1584047/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

I am delighted to review Rødland’s work. Swahili Social Landscapes makes an important and thoughtful contribution to our study of Zanzibar’s rich history. Based on her doctoral dissertation, it focuses on the “social and productive landscapes” of Tumbatu and Mkokotoni. Tumbatu is an island off the northwestern coast of Unguja (Zanzibar) Island, while Mkokotoni lies on Unguja itself, across the channel from Tumbatu. Both sites were occupied between the 11th and 15th centuries CE.

This study questions traditional narratives of the Swahili that are based exclusively on Indian Ocean trade networks, Islam, stone towns, and hierarchically organised societies. Instead, Rødland explores how Swahili social identity and status were expressed through labour, foodways, gender, and material culture. In short, she seeks to decentre much of the focus of Swahili archaeology until now, looking instead at how social identities were created and maintained by other means. Thus, rather than focusing on how elites gained status through a display of imported ceramics, Rødland examines how space, craft production, and its attendant knowledge were all used to create and maintain identities. As Rødland points out, even though Tumbatu and Mkokotoni were part of ‘the Swahili World’, both sites revealed scant evidence for status distinction. Rødland interprets this to mean that imported material culture was not monopolised by an elite, but rather was available to most of the population.

Rødland’s assertion that the two sites were “neighbourhoods” of the same settlement, with Tumbatu being devoted to trade and Mkokotoni devoted to production, is backed up by strong evidence. It is difficult to disagree with her conclusion that space and its use played a powerful role in the creation of social identities.

My hope is that Rødland’s work will serve as a model for future conversations about the Swahili and the creation of identity. As Rødland notes, the term “Swahili” itself has been in use only for 200 years, and it is a term originally used by Omani Arabs to refer to some of the local population. Rødland’s wry observation that no one consulted the Swahili about their preferred identity hits home, especially in archaeological studies, where “Swahili” is used to describe peoples on the East African coast for at least the last millennium.

All in all, Rødland’s work shows us the importance of breaking from traditional narratives about the Swahili, and in exploring new ways in which precolonial African populations conceived of themselves and generated social identities. Hopefully, Rødland’s work heralds a new phase in the archaeology of the East African coast, where more nuance and sensitivity is employed to understand the past.

Akshay Sarathi

Akshay Sarathi is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Florida Atlantic University. His research concerns the movement of meat across landscapes. His current work is focused on the site of Unguja Ukuu, Zanzibar.

THE SLOPE OF KONGWA HILL: A BOY’S TALE OFAFRICA. Anthony R. Edwards. Agio Publishing House, Victoria BC, Canada, 2011. 420 pp. (paperback). ISBN 978-1-897435-65-6. £22.89. Also available as an e-book: a pdf sampler can be downloaded from the publisher’s website here: http://www. agiopublishing.com/authors/tonyedwards/.

Kongwa town, 60 miles east of Dodoma, will be known to readers, first, for the cattle ranch of the National Ranching Company (NARCO), and secondly, for the British government’s notorious and ill-fated Groundnut Scheme of 1949-52 (reviewed in Tanzanian Affairs 129). But the Scheme left a legacy which is less well-known – first, the good health of the local people, nourished on a plentiful supply of groundnuts, and secondly, the establishment of Kongwa School for European children.

This book is the story of that school, seen through the eyes of a boy whose father served as Mayor of Lindi. Hundreds of children from many parts of East Africa attended the school from 1949 to 1958, when it moved to Iringa, until it was liquidated with the approach of independence. True to the English public school tradition, it featured fagging, bullying and corporal punishment – a life of misery for young children snatched from their mothers’ arms sometimes at far too young an age, but exciting for older teenagers who were asked to bring their rifles to school so that in times of meat scarcity they could go out and hunt their own. The beginnings of romantic experiences in this mixed school are described, also the hospitality and kindness received from local villagers on the rare occasions when a group of children broke bounds to go exploring. Even incursions from the Mau Mau of Kenya were thought to be a threat, but the incident when they set up camp near the school, communicating with one another by Morse code, was found to be a fictional tale invented by one boy’s over-fertile imagination.

Remnants of those far-off days are still visible – the English style village church on the hillside, the swimming pool, the hospital, the teachers’ houses called ‘Millionaires’ Row’, the railway station – all inherited from the Groundnut Scheme. Perhaps the most significant legacy is the local Mnyakongo Primary School, with 800 pupils using the same old buildings. In 2008 a group of now quite ancient alumni paid a nostalgic visit to their old School and were so warmly welcomed by the teachers and children of Mnyakongo that they have set up an ongoing partnership, with gifts of books and equipment, described in an appendix with a collection of photographs of those far off days both in Kongwa and in Lindi.

This book is a snapshot from the ‘bad old days’ of colonialism, but the school left in the minds of those boys and girls a love of Africa and a respect for Africans which makes old sentiments of racial superiority or segregation quite meaningless, and is bearing fruit 70 years later. The book is an easy read, interspersed with Swahili and Cigogo and full of personal touches.

Roger Bowen

Roger Bowen taught at St Philip’s Theological College, Kongwa, in the 1970s and chaired the Swahili Theology Textbooks programme of East Africa.

PROTECTED AREAS IN NORTHERN TANZANIA: LOCAL COMMUNITIES, LAND USE CHANGE, AND MANAGEMENT CHALLENGES (GEOTECHNOLOGIES AND THE ENVIRONMENT 22). Jeffrey O. Durrant, Emanuel H. Martin, Kokel Melubo, Ryan R. Jensen, Leslie A. Hadfield, Perry J. Hardin, and Laurie Weisler (editors). Springer, Cham, Switzerland, 2020. viii + 179 pp. (paperback). ISBN: 978-3-030-43304-8. £69.99. Also available in hardback and as an e-book.

This edited collection of papers on Protected Areas in Northern Tanzania is the outcome of a collaboration between the College of African Wildlife Management at Mweka and researchers – mostly geographers – at Brigham Young University in the United States. Following a foreword by the Rector of Mweka, Professor Jafari R. Kideghesho, the volume is introduced with a brief overview of Tanzania’s protected area system and its history by Jeffrey O. Durrant and Rebecca Formica. This introductory chapter is followed by eleven more on different aspects of protected area and natural resource management in northern Tanzania.

In order to give potential readers a fair idea of this book’s varied contents, the following paragraphs are taken from the summary that is tacked onto the end of the opening chapter:

“Chapter 2 illustrates some of the real costs of population growth and modern society’s move toward mass production of agriculture, such as at coffee plantations. While cavity-nesting birds have done well in protected areas, [Hamadi] Dulle et al. found the birds are facing some irreversible forces through population growth and changes in land use outside of protected areas. Dulle et al. found that heavy losses of deadwood near coffee plantations are negatively impacting cavity-nesting birds. Dulle et al. examined the effects of providing artificial nesting boxes and suggest them as one option to address losses of these nesting birds that is seen as irreversible.

[Leslie] Hadfield takes a historic look at how Africa’s colonial past is impacting current tourist interaction with the porters and guides on Mount Kilimanjaro (Chap. 3). Hadfield examines how some attitudes from the use of porters in colonial expeditions have evolved to modern-day tourism. Even with current porter organization efforts to prevent colonial-type practices that require constant service to outsiders with little regard for the health and well-being of the local porters and guides, challenges such as heavy loads, poor equipment, and inadequate food and safety remain.

Looking at Arusha National Park, [Obeid] Mahenya [and Naomi Chacha] (Chap. 4) study how the individualized impacts to those living nearby affected their attitudes toward the Park. Mahenya et al.’s [sic] study found that the attitudes of locals were more positive toward Arusha National Park in relation to giraffes, since giraffes present few problems to the residents and are associated with the positive benefits of tourists. However, more negative attitudes resulted from interactions with more destructive animals such as baboons or when people had been fined for domestic livestock grazing in the Park.

Similarly, [Kokel] Melubo et al. (Chap. 5) found that having personal experiences in protected areas contributed to better attitudes and ability to manage protected areas. Melubo et al. studied students at CAWM who had been involved in a wilderness training program that involved at least a short overnight experience in a protected area. Students who participated in these programs were found to be better equipped to operate and manage protected areas in their future careers.

Extending the theme of effective protected area management, [Rehema Abeli] Shoo evaluates the impact of having an effective management structure in place on the success of ecotourism (Chap. 6). Shoo found that a sound management plan can help managers avoid obstacles that often prevent successful ecotourism, such as environmental deterioration and inequitable development among the local communities. Shoo studied Lake Natron, which has a high potential for ecotourism development However, Shoo found that without a sound general management plan, Lake Natron suffered from inadequate funding at the operational level, lack of mechanisms to secure a fair distribution of ecotourism benefits, and poorly developed tourism infrastructure and facilities that reduced the potential for successful ecotourism at the park.

[Alfan] Rjia and [Jafari] Kideghesho examined nine poacher’s strategies used in the Serengeti ecosystem (Chap. 7). They argue that increased enforcement of wildlife crimes has influenced adaptability in poacher’s strategies. Field rangers and wildlife managers can use the nine strategies they described to more effectively combat wildlife crimes, and the authors provide three recommendations to help inform field patrols and other mitigation efforts.

In Chap. 8, [Alex] Kisingo and [Professor] Kidegheso present findings from previous community governance studies using a V3 model. They found some changes in community governance with regard to conservation, livelihood improvement, and social benefits. They also note some setbacks in community governance that need to be addressed. Several chapters examine biophysical characteristics of protected areas in northern Tanzania.

[Emmanuel] Martin et al. (Chap. 9) used temporal remote sensing data to study land use and land cover change near the Kwakuchinja Wildlife Corridor in northern Tanzania. They found that while a paved road provided better connections between two towns, it also impacted animal movement between two national parks by providing a physical obstacle and bringing in more settlement. Satellite remote sensing data showed that over time, the most significant changes were from bare ground to “savanna with some agriculture” and “agriculture with some grassland.”

[Gideon] Mseja et al. used transect lines in Mkomazi National Park to count wild animals as ground reference information for the population density (Chap. 10). A total of 22 species were estimated, and African Buffalo (Syncerus caffer) was the most common species, while Gerenuk (Litocranius walleri) was the least. Mseja et al. suggest other methods be used to count more elusive species. For example, camera traps could be used to estimate carnivores and dung counts for elephants. The combination of these methods can give a benchmark for future population estimates.

In Chap. 11, [Emmanuel] Martin et al. used MODIS land cover data and scripts in Google Earth to examine vegetation change within Mkomazi National Park in northeastern Tanzania both before and after it became a national park in 2008. The data showed relatively subtle changes and most likely reflect that only subtle changes in land management policy have occurred since its conversion from two separate game reserves.

Finally, in Chap. 12, [Professor] Kideghesho et al. review the challenging dynamics between wildlife conservation and human population growth and urbanization. The authors provide recommendations on the best manner to minimize the negative impacts of human population growth on large mammals.”

As this summary indicates, this is very much a mixed bag of papers, and there isn’t a very strong or even coherent theme to the volume. The nature of the collaboration between the two institutions involved is not explained, and the book appears to have been assembled hastily and without proper proofreading. A paragraph introducing the above summary of chapters is repeated word for word, except that the first time round (on p. 11) it states that the book has eight further chapters, and the next time (on p. 12) it says ten, when there are actually eleven more chapters.

This is not good enough for a publisher of Springer Nature’s status and such a costly volume. No doubt many researchers will find something of interest in this collection, but I suspect that most would rather consult it in a library than dig into their purses and wallets.

Martin Walsh

Martin Walsh is the Book Reviews Editor of Tanzanian Affairs.

Also noticed:

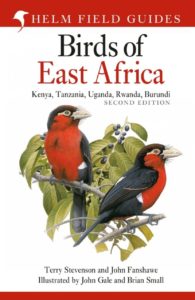

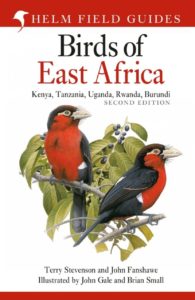

BIRDS OF EAST AFRICA: KENYA, TANZANIA, UGANDA, RWANDA, BURUNDI. SECOND EDITION (HELM FIELD GUIDES). Terry Stevenson and John Fanshawe. Illustrated by John Gale and Brian Small. Helm, London, 2020. 640 pp., 287 colour plates (paperback). ISBN: PB: 978-1-4081-5736-7. £31.50. Also available in hardback and as an e-book.

This new edition of Birds of East Africa substantially updates the first, which appeared in 2002 and is described by the publisher as “the best-selling Helm field guide of all time” – a reflection, in part, of its comprehensiveness and the popularity of birding in East Africa. The authors describe the changes they have made to the species accounts as follows:

“This second edition covers 1,448 species, which represents around 70% of the birds that have been recorded in sub-Saharan Africa. […] Recent taxonomic changes include the creation of three new families: Modulatricidae, Nicatoridae, Hyliotidae.

Although our knowledge is steadily increasing, there is still an enormous amount to learn about East Africa’s birds. New species and races are still being described: Udzungwa Forest-partridge, not only a new bird but also a new genus to science, was found in the montane forests of south-central Tanzania in 1991. New species in this edition include range extensions, taxa now considered specifically distinct, and additional scarce and vagrant species.

In our first edition, the taxonomy and nomenclature were largely based on the East African list that was published in 1980 (Britton, P. L. 1980, Birds of East Africa, East Africa Natural History Society). Since then, the growth in birding and citizen science worldwide has seen the emergence of four major global lists: the IOC World Bird List, the Howard and Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World, the eBird/Clements Checklist of Birds of the World (in collaboration with Cornell University), and the HBW (Handbook of the Birds of the World) and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist. All of these lists are compared online by the comprehensive and regularly updated resource, Avibase.

While taking close account of the first edition and the three other global lists, we have chosen to base the majority of this revised Birds of East Africa on the HBW/BirdLife taxonomy and nomenclature. Throughout, we have provided alternative common names, as well as explaining any scientific name changes in notes. Although this means that a number of changes in common names have occurred, we hope that it actually represents a move towards wider stability in names, both in East Africa and worldwide. If hyphens and capitalisation are excluded, there is agreement on 85% of the common names in the HBW/ BirdLife, IOC and eBird/Clements lists. For the birding community, working together to agree and stabilise taxonomy is crucial for citizen science and conservation.”

As this implies, birders will always find something to quibble about. But whichever way you look at it, this is a superb resource. My main wish, as with the first edition, is that arrows had been used on the distribution maps to indicate the presence of species on the region’s larger islands. Those tiny splotches of colour can be hard to see without a magnifying glass.

Martin Walsh