by Martin Walsh

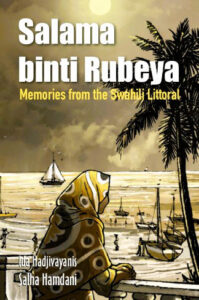

SALAMA BINTI RUBEYA: MEMORIES FROM THE SWAHILI LITTORAL. Ida Hadjivayanis and Salha Hamdani. Mbiu Press, Dar es Salaam, 2025. ISBN 9789912752238 (paperback). TSh 15,000. Also available to rent as an e-book: https://lantern.co.tz/books/salama-binti-rubeya-memories-from-the-swahili-littoral-9789912752238

Marriage. A word that once meant nothing but love to me, noble, selfless, pure. As I grew older, I began to see the cracks in that simplicity. Marriage, I’ve come to realise, is layered, complicated, and never just about romance.

Reading Salama Binti Rubeya: Memories from the Swahili Littoral by Dr. Ida Hadjivayanis and Bi. Salha Hamdani deepened that understanding. In its pages, marriage becomes more than love. It is a symbol of freedom, independence, and a transition from girlhood into womanhood.

We follow Salama binti Rubeya’s life in the 1910s, as remembered by her daughter, Salha Hamdani, and her granddaughter, Dr. Ida Hadjivayanis. These memories, some drawn directly from recorded interviews, others recalled through family stories, create an intimate portrait of a resilient woman whose life carried the weight of history.

“Salama’s narrative lets us into a world that once was and allows us to see a retelling of a certain event in history through the eyes of a woman.”

East African history has often been recorded by academics, with little space for the voices of ordinary citizens. This book shows that powerful narratives can also emerge from women like Salama, whom Dr. Ida refers to as “an unassuming woman” in the coastal story.

The book bridges formal history with lived memory, demonstrating how family stories intersect with those of scholars. It does not reject the work of historians but complements it by placing Salama’s memories alongside academic research. In this way, it demonstrates how personal experience can add depth to written history, providing readers with a fuller understanding of the past.

Salama’s childhood highlights how gender roles defined daily life. As a girl in Kilwa, she was free to move within the world of women, listening to her grandfather’s conversations with guests until age forced her behind a curtain. It was from that hidden corner that she first saw Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Hamdani, the man who would become her husband and the father of her children.

“She was free to roam the world of women, indoors, but it is through a curtain that she gets glimpses of the world of men. To her, it feels almost revolutionary because she did get to hear more than what most women around her ever did.”

Within this world, women were barred from school and excluded from social life unless they were wives or accompanied by men. Marriage and divorce became some of the few routes to freedom and self-determination. It was not unusual for women to marry multiple times without shame. Salama’s mother, Binti Mbwana, remarried after her husband’s death. As a widow, she lacked the liberty of a married woman or even a divorcee.

“Salama believes that she remarried because she missed her social life and the liberty that came with marriage rather than falling in love with the man.”

Stories like Salama Binti Rubeya’s show how marriage has evolved. Today, it carries a different meaning, raising questions about whether those changes have improved or worsened it. This makes the book a compelling read for anyone interested in social issues.

Race, identity, class, and ethnicity also run through these pages. When Salama moved to Zanzibar, a cosmopolitan port shaped by the Indian Ocean trade, she encountered rigid hierarchies. Arabs from Oman controlled most of the land, and Salama observed how wealth and privilege were unequally distributed.

Another theme is the importance of female friendship and sisterhood. Such relationships offer women a safe space to heal, to share their struggles without fear of judgment. From Salama’s mother to Salama herself, we see how friendship provided a sense of belonging and a vital outlet. For Salama, sisterhood took shape in her neighbourhood, built on common interests such as food, fashion, and art.

“In fact, women used to walk together and return home together as they discussed the film they had just watched. For a week or so following the screening, women would discuss the film, link it to reality, and draw new conclusions.”

Salama Binti Rubeya: Memories from the Swahili Littoral sheds light on the struggle for independence, the Zanzibar Revolution, and its aftermath for Salama’s family. Her son, Abdulrahman Guy, the primary breadwinner, bore the brunt of this turbulent period. His fate was another testament to Salama’s resilience and endurance.

A reminder that history is not just a collection of dates and events, but the choices and struggles of people like Salama. It is for anyone who wants to understand the Swahili littoral through the lived experience of a woman who was curious, multicultural, and unapologetically herself. It takes us through Zanzibar and Kilwa before colonialism, into the revolution, and its aftermath. Above all, it reminds us why telling our stories matters.

(This review was first published in The Citizen newspaper: https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/tanzania/magazines/success/-salama-binti-rubeya-memories-from-the-swahili-littoral-by-ida-hadjivayanis-salha-hamdani-5193638.)

Jane Shussa

Jane Shussa is a Tanzanian writer, digital communications specialist, and weekly book reviewer for The Citizen newspaper. A storyteller committed to sharing and amplifying East African stories and perspectives, she invites readers to discover new books. Outside the pages, she enjoys hiking, savouring coffee, caring for her plants, and watching the sky.

MWALIMU JULIUS KAMBARAGE NYERERE: PHOTOGRAPHIC JOURNEY. Mama Maria Nyerere (introduction), Palamagamba Kabudi, Kumail Jafferji, Mahmoud Thabit Kombo, Ali Sultan (text), Adarsh Nayar (photographs), Javed Jafferji (photo editor). Print Plus Media Ltd, Zanzibar, Zanzibar, 2024. 350 pp. ISBN 9789912989917 (hardback) US$40.00. Available from TPH Bookshops in Dar es Salaam and Dodoma, and Zuri Rituals Boutique in Zanzibar.

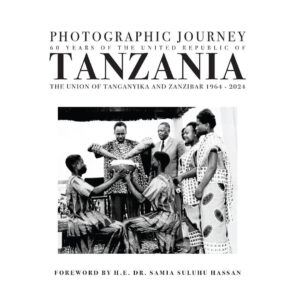

PHOTOGRAPHIC JOURNEY: 60 YEARS OF THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA, THE UNION OF TANGANYIKA AND ZANZIBAR 1964-2024. Mahmoud Thabit Kombo Jecha and Kumail Jafferji (eds.). Print Plus Media Ltd, Zanzibar, 2024. 232 pp. ISBN 9789912416321 (hardback) US$40.00. Available from TPH Bookshops in Dar es Salaam and Dodoma, and Zuri Rituals Boutique in Zanzibar.

These two remarkable books constitute a photographic reflection on first the life of Julius Nyerere and second the history of the Union. Whilst the numerous photographs spread between the two books are an excellent historical archive the text in both cases constitutes an authoritative exposition of both Tanzania’s modern history and also of many aspects of Nyerere’s life from student days to his death in 1999. Both books include a foreword by President Dr Samia Suluhu Hassan which are an eloquent statement of how much she and many Tanzanians owe to his example and inspiration.

The book devoted to Nyerere embraces a host of photographs which capture the long arc of his life, whilst containing some surprising nuggets. These range from the fact that he wrote and published a book whilst in his second year at Makerere entitled Uhuru wa Wanawake, translated into English as Women’s Freedom: Women are Eagles Not Chickens. The proceeds from the book were used to establish a scholarship fund for female students at Makerere (which is still active). Secondly, the hard-won victory in the war with Uganda in 1979 was assisted by the supply by Algeria of Russian missiles.

The photographic highlights of the book include:

-A handshake with Mao Zedong in 1965, a subsequent address to a rally in Beijing, a walk hand-in-hand with Zhou Enlai, and a tea party with Mao, Zhou Enlai and Liu Shaoqi;

– Formal and informal meetings with all the heads of the ‘Frontline States’, each of which owed a debt to Tanzania for her support before they achieved independence;

-Meetings surrounding the making of the Union in 1964, notably with both Abeid Karume (who became his Vice President) and Sheikh Thabit Kombo (who is described as a key link for Nyerere into Zanzibar’s Revolutionary Council);

– Joan Wicken, Nyerere’s personal secretary who shared his political ideals and drafted some of his key speeches;

-An address to the parliament in Cape Town, the rewarding consequence of more than 30 years of support for the ANC and its military wing based in Tanzania;

-A visit with Fidel Castro to a training farm at Ruvu in 1977.

The text of the book is greatly strengthened by a description of 40 “key relationships” which ranges from his close associates in government (including the first women cabinet ministers), including his long-standing VP Rashidi Kawawa and highly-regarded Foreign Minister Salim Ahmed Salim, and extends to twenty heads of state, with a clear discussion of their relationships with Nyerere.

Whilst there are now many biographies or semi-biographies of Nyerere, this amalgam of text and the photographic record are a unique tribute to the life of this extraordinary man and leading statesman.

It is balanced by a photographic history of the Union, which is an update of an earlier book that covered 50 years rather than 60, first published in 2014. The new edition points out that nearly 70% of today’s Tanzanians were born after the Union of 1964, making records of this kind particularly important. Its photos range from a celebration by ivory traders of a large set of elephant tusks to the railway train to Bububu opened in 1905. It neatly captures the fragility of the newly-elected Sultan’s government of December 1963 with a picture of Karume being presented to Sultan Jamshid. It does not flinch from a fairly unvarnished account of the subsequent revolution, although it downplays the role of that most elusive figure, John Okello. It captures the ‘western’ response to the revolution by quoting the New York Times declaring after the revolution that “Zanzibar was on the verge becoming the new Cuba”.

The text is far from sycophantic and accurately describes both the enthusiasm surrounding the Arusha Declaration in 1967, and its quasi-reversal in the Zanzibar Declaration of 1991.

The combination of photographic history and the text make this both an excellent record of the Union and a valuable summary of many of the cornerstones of its story. It is unfortunate that for the time being the books are only available in Tanzania, a situation hopefully to be corrected before long.

Laurence Cockcroft

Laurence Cockcroft is a development economist who worked in Tanzania (at ‘Devplan’ and TRDB) from 1970-72 and subsequently helped to establish the Tanzania Gatsby Trust where he was a Trustee from 1985 to 2015. He is also a co-founder of Transparency International and has written and spoken widely on questions surrounding global corruption.

Also noticed:

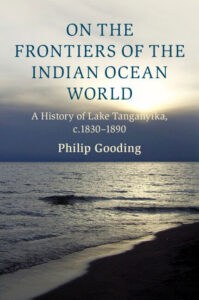

ON THE FRONTIERS OF THE INDIAN OCEAN WORLD: A HISTORY OF LAKE TANGANYIKA, c. 1830-1890. Philip Gooding. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2022. xiii + 251 pp. ISBN 9781009100748 (hardback) £78.00. ISBN 9781009114189 (paperback) £29.99; ISBN 9781009122023 (online) £29.99.

This welcome and well-received book by Philip Gooding at McGill University in Montreal is published by Cambridge University Press in the Cambridge Oceanic Histories series and described by them as follows:

“This is the first interdisciplinary history of Lake Tanganyika and of eastern Africa’s relationship with the wider Indian Ocean World during the nineteenth century. Philip Gooding deploys diverse source materials, including oral, climatological, anthropological, and archaeological sources, to ground interpretations of the better-known, European-authored archive in local epistemologies and understandings of the past. Gooding shows that Lake Tanganyika’s shape, location, and distinctive lacustrine environment contributed to phenomena traditionally associated with the history of the wider Indian Ocean World being negotiated, contested, and re-imagined in particularly robust ways. He adds novel contributions to African and Indian Ocean histories of urbanism, the environment, spirituality, kinship, commerce, consumption, material culture, bondage, slavery, Islam, and capitalism. African peoples and environments are positioned as central to the histories of global economies, religions, and cultures.”

There’s a lot for other researchers to build on here, as well as gaps to fill, for example in considering the impacts of the above on language use around the lake and beyond, and by using linguistic evidence itself as a historical source. While we can’t expect all historians to be linguists, an understanding of the basics does help, as Gooding illustrates by his eccentric decision to anglicise Swahili and other vernacular terms by chopping off their noun class prefixes. Unfortunately, he does this inconsistently and sometimes wrongly. The result is a muddle of conventional usage and unfamiliar neologisms that make little sense without the glosses supplied. It’s embarrassing that the examiners and other readers of the author’s work as it evolved from doctoral dissertation (SOAS, 2017) into book did not pick this up, and it detracts from the author’s otherwise fine scholarship.

Martin Walsh

Martin Walsh is the Book Reviews Editor of Tanzanian Affairs.

KENYA’S SWAHILI COAST: FROM THE ROMAN EMPIRE TO 1888.

Judy Aldrick. Old Africa Books, Naivasha, Kenya, 2024. 256 pp. ISBN 9798320843643 (paperback) £13.99.

Although its primary focus is on Kenya, there’s much in this book that’s relevant to the history of the East African coast as a whole. It’s been written for a general audience by Judy Aldrick, whose work will be familiar to many with an interest in the region’s past (see https://www.historyofeastafrica.com/, where her regular newsletter on Kenyan coastal history can also be found). Here’s her own summary of what’s in store for readers of her latest book:

“The story of the Swahili Coast is full of drama and adventure, unexpected twists and turns and visitors who came and went and left their mark. As far back as Roman Times the East African Coast was part of a well organised trade network. The Islamic era brought in wealth and settlement, then came the Portuguese and a period of disruption. Swahili civilisation hung in the balance, until Arabs from Oman moved in revitalising the Coast but also bringing in petty squabbles as ruling families and towns fought for power. Zanzibar emerged victorious and wealth started to flow back into the region, until Europeans began to interfere.

There are facts and dates but also tales of myth and magic, of unsolved mysteries, tragic heroes and cruel villains. In a brutal age, life was lived in the raw. Treachery and betrayal and reckless action caused dangerous moments of peril, while expediency and pragmatic diplomacy often saved the day. Throughout the narrative the resilience and survival of the Swahili people shine through.

The cut-off point is set at 1888 when modern history of Kenya begins, and there is no longer separation between Coast and hinterland.”

Martin Walsh

SWAHILI FOR DUMMIES. Seline Okeno and Asmaha Heddi. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey, 2024. xii + 352 pp. ISBN 9781394191567 (paperback) £18.99; ISBN 9781394191574 (e-book) starting at £14.99.

According to the publisher’s blurb, “Swahili For Dummies will teach you the basics of Swahili, so you can start conversing in Africa’s language of commerce. This book introduces you to the foundations of Swahili grammar and enables you to engage in basic conversations. With the simplified Dummies learning process, you’ll quickly get a grasp on the language, without complex terms and confusing explanations. You’ll also move through the book at a comfortable pace, so you’ll be familiar with what you’ve learned before moving on to more complex stuff. Focus on communication and interaction in everyday situations, so you can actually use the language you’re studying – right away.

-Understand the basics of Swahili

-Learn everyday words and phrases

-Gain the confidence to engage in conversations in Swahili

-Communicate while traveling and talk to Swahili-speaking family members

“Swahili For Dummies is for readers of all ages who want to learn the basics of Swahili in a no-stress, beginner-friendly way. Swahili teachers will also love sharing this practical approach with their students.”

Moreover, if you reach page 287, you’ll find your vocabulary being enriched by “Ten Words You Should Never Say in Swahili”, including words and phrases that are only rude when used to describe humans rather than animals. You’ll also learn some up-country misspellings. But providing this kind of list isn’t a bad idea, especially for those hapless tourists who are trained to utter insults by beachboys pretending to teach them everyday Swahili greetings. As well as such greenhorns, the book as a whole might also be of value to those needing to brush up on basics like the structure and use of noun class prefixes.

Martin Walsh