by Ben Taylor

The CAG report dominated front pages on Nov 27th (millardayo.com)

For a week in November, the attention of Tanzania’s political scene was diverted away from the constitution and the 2015 elections and onto yet another energy sector corruption scandal – the IPTL Escrow case. The long-awaited report of the Controller and Auditor General (CAG) into the case was presented to the Parliamentary Accounts Committee (PAC) which in turn reported the key findings back to parliament.

That the report was presented at all was a triumph for parliamentary procedure and for a few determined MPs, including the Speaker, Anna Makinda, who resisted reported attempts by the judiciary, the Prime Minister and others to block the debate.

The scandal saw more than £116m taken from an escrow account at the Bank of Tanzania and transferred to offshore accounts held by private businessmen and government officials, according to Zitto Kabwe, the firebrand opposition (Chadema) MP and PAC chair. Kabwe presented the report to parliament together with the PAC deputy chair, Deo Filikunjombe (CCM).

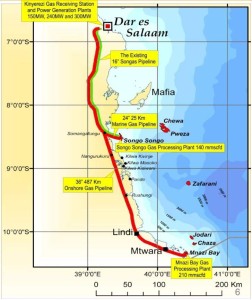

The escrow account was opened in 2006, following a disagreement over charges to be paid by Tanesco, the national energy utility, to IPTL for emergency power generation. Tanesco was to deposit money in the account until such a time as the disagreement over charges could be resolved.

The ownership of IPTL has since changed hands, and a Tanzania-born Kenyan businessman, Harbinder Singh Sethi, now claims to be the legitimate owner of the firm, and that the funds in the escrow account were rightly his.

The case hinges principally on two issues: who is the rightful owner of IPTL, and did any or all of the money in the escrow account belong to the government and/or Tanesco?

The Parliamentary Accounts Committee said that irregularities in the sale of IPTL to Sethi’s company, Pan-African Power Solution (PAP) meant he was not the proper owner of the firm. Citing the support of the Controller and Auditor General, the Director General of the Prevention and Combatting of Corruption Bureau (PCCB) and the Commissioner of the Tanzania Revenue Authority (TRA), the committee argued that most of (or all) the funds in the escrow account were the rightful property of Tanesco.

Attorney General Frederick Werema, Minister of Energy and Minerals Professor Sospeter Muhongo, Prime Minister Mizengo Pinda and later President Kikwete all disagreed, arguing that Sethi was the owner of IPTL, and that the escrow account funds were his.

The case has already brought a heavy financial toll to Tanzania. In addition to the money allegedly stolen from the public purse, the UK and eleven other international donors have suspended $490m in general budget support for the current financial year, citing the slow pace of investigations into the case. More recently, the Millennium Challenge Corporation, a US aid agency, indicated that they were monitoring developments closely and warned that their decision on a new funding agreement – potentially several hundred million dollars – would depend on the Tanzanian government acting swiftly and decisively to combat corruption.

In presenting his committee’s report, Kabwe drew both shock and laughter as he explained that the Director General of PCCB had confirmed that people had collected funds in cash from the Mkombozi and Stanbic bank branches in plastic carrier bags, cardboard boxes, and sisal gunny sacks. As much as Tshs 73.5bn ($45m) was reportedly withdrawn on a single day in January 2014.

In his response to the parliamentary debate and resolutions, delayed by his health condition, President Kikwete spared the Minster of Energy and Minerals, Prof Muhongo, though parliament had called for his sacking. Instead, the President said that he has formed a team to investigate the Minister, and will make a decision once the team has reported back to him.

Prime Minister Pinda also survived when parliament revised the initial recommendation of the PAC that he should step aside.

In December the scandal claimed two senior scalps. Attorney General Werema, resigned on 17 December, though he denied any wrongdoing and said he was stepping down because his legal advice had been misunderstood. A few days later, President Kikwete sacked the Minster of Lands, Housing and Human Development Anna Tibaijuka for accepting a $1m payment from a Tanzanian businessman James Rugemalira, linked to the case.

Rugemalira had sold his 30% stake in IPTL to Sethi for $75m, and is alleged to have then transferred significant money into accounts held by a long list of public figures, including $1m to Mrs Tibaijuka. She does not deny receiving this amount, but claims that she was merely channelling the money onwards to a school. Other reported beneficiaries of Rugemalira’s generosity were senior political figures such as former Attorney General and veteran of the BAE-radar scandal, Andrew Chenge, two former Ministers of Energy and Minerals, William Ngeleja and Daniel Yona, and board members and employees of Tanesco, the Tanzania Revenue Authority, the Tanzania Investment Centre (TIC) and the Registration, Insolvency and Trusteeship Agency (RITA), as well as two judges and two bishops.

The political impact of the scandal, particularly in terms of the forthcoming elections may be significant. Pinda, a leading candidate for the CCM presidential nomination, has been weakened in the public eye. Anna Tibaijuka is no longer a viable candidate. The Speaker, Anna Makinda, an outside possibility for the nomination, surprised many with her strong handling of the affair – standing up to powerful figures, protecting parliamentary independence, and chairing heated discussions with considerable dexterity.

Other leading potential CCM candidates for the presidency did their best to stay out of the fray. Edward Lowassa and Bernard Membe were notably quiet, in public at least, and January Makamba spoke only in general terms that corruption should not be tolerated.

Though Chadema (aside from their renegade member, Zitto Kabwe,) was late to exploit the case, the party is likely to pick up some votes from the affair, simply because it makes CCM look bad.

Beyond the presidential race, several MPs’ reputations were enhanced. David Kafulila (NCCR-Mageuzi) earned plaudits for his long-standing campaign to bring this case to public attention. Zitto Kabwe’s forensic skill and determined handling of the PAC has been noted, and there are signs of a possible thawing of his previously frosty relations with his Chadema party leaders. Deputy PAC chair Deo Filikunjombe (CCM), was visibly nervous in presenting the report, and spoke later of his discomfort in calling for the resignation of a Prime Minister who was seated just a few feet away. Though his public reputation has been enhanced, he has lost popularity with some senior party figures, and may therefore face a difficult re-selection process in his Ludewa constituency.

Anti-corruption investigators continue to look into the case, and promise prosecutions where appropriate. Despite the pressure being exerted by donors, this may or may not happen. Though two senior government figures have lost their jobs, the suspicion remains that many others – including senior figures within State House – have got off lightly.

In November the Executive Director of Tanzania Legal and Human Rights Centre Dr Hellen Kijo-Bisimba said President Kikwete failed to take a bold decision on the scandal and in turn acted “like an advocate of Pan African Power Solution.” Even Zitto Kabwe showed little appetite to take the matter further. “As Parliament we passed the resolutions by consensus, patriotism and avoiding being unfair to anyone. Parliament did its work ….and I’m leaving this matter to wananchi, they will make their own judgement,” he said.

The leader of opposition and chairperson of Chadema Mr Freeman Mbowe said by failing to sack the architects of the scandal the President showed the country that he is part of the wider corruption problem. “Anna Tibaijuka was but a branch of the scandal, so she was used as a scapegoat, while [those who] orchestrated the whole thing are yet to be touched,” he said.

A political science professor from Ruaha University College, Gaudence Mpangala, said the President did not arrive at decisions that were awaited by many in the country. “By saying that the escrow monies belong to IPTL, the President blew the whole thing away and that is very wrong,” he said.