edited by John Cooper-Poole

RACE, NATION AND CITIZENSHIP IN POST-COLONIAL AFRICA: THE CASE OF TANZANIA. Ronald Aminzade, Cambridge University Press, 2013. £65.00

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF TANZANIA: DECLINE AND RECOVERY. Michael Lofchie, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014. £39.00

TOXIC AID: ECONOMIC COLLAPSE AND RECOVERY IN TANZANIA. Sebastian Edwards, Oxford University Press, 2014. £35.00 These books report in contrasting ways on Tanzania’s experiences since Independence in 1961. Aminzade’s book is as a study of race and nation-building, starting with the tensions between those who wanted immediate Africanisation before and after Independence and the ambiguous positions taken by Nyerere and other leaders towards Asians and expatriates, and ending with the grand corruption of the last 15 years or so, in which Africans worked closely with Asian businessmen. Lofchie describes his book as a political economy, in which he interprets much of what happened in the 1980s and later from the financial interests of the “political-economic oligarchy” who could gain from maintaining an overvalued exchange rate in the 1980s (and therefore were not committed to devaluation) but by the late 1990s discovered that they could gain even more from unrestricted trade and an open economy – they were making the transition to becoming a business class.

Edwards uses a study of the relationships between Tanzania and its aid donors to capture what was happening at the centres of economic power. It turns out that the “toxic aid” of his title refers to the period from the Arusha Declaration of 1967 up till the early 1980s when foreign aid, particularly from the Nordic countries and the World Bank, kept the country afloat. He castigates them for uncritically maintaining Nyerere’s brand of socialism, and uses words such as ‘irresponsible,’ ‘arrogant,’ ‘misguided,’ ‘gullible,’ ‘ineffective,’ and other equally tough terms to describe their behaviour. In contrast, he grades Tanzania’s current donors as B+, for having spoken out against corruption, and worked to increase transparency and democracy.

All three authors are academics in American universities, but from different backgrounds. Aminzade is a sociologist and historian who studied the emergence of nationalism in France for 20 years and first came to Tanzania in 1995. Lofchie, from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), is best known for his authoritative tract on the revolution in Zanzibar which led to the union with the mainland, published as long ago as 1965. He has written widely on development, especially in Africa. Edwards is a Chilean economist, trained at the University of Chicago, also at UCLA where he is professor of International Business Economics. He first went to Tanzania in 1991, when the country was at one of its lowest ebbs, employed by the World Bank and given a desk in the Bank of Tanzania, returning in 2009 and subsequently. His perspective is that of a Latin American specialist who has turned his hand to an African country.

Anyone writing about Tanzania has to take a view of Nyerere. Aminzade is the least clear-cut. He portrays Nyerere as an honest and intelligent leader constantly fending off demands for rapid Africanisation, but often only with compromises. Lofchie provides the most sympathetic interpretation of what Nyerere was trying to achieve in the 1960s. He sees him as a thoughtful, well intentioned, humanist, Fabian in terms of his uses of state power, but suggests that he got carried away after the banks and major industries were nationalised in 1967, and did not realise the dire consequences of the industrialisation strategies of the Second Five Year Plan and the attempts of the state to take over trade and the purchasing of maize and other food crops from farmers. Edwards, in contrast, sees Nyerere as a misguided but plausible ideologue, unwilling to listen when told there was no alternative to devaluation in the 1980s.

The core of both Edwards’ and Lofchie’s accounts is the structural adjustment that took place between 1979 and 1996, and the economic policies which have led to rapid growth since. Edwards interviewed many of those closest to Tanzanian economic policy-making: Cleopa Msuya, Gerry Helleiner, Sam Wangwe, Ibrahim Lipumba and Benno Ndulu. He draws on his experiences in the Bank of Tanzania and especially his friendship with Edwin Mtei, Governor of the Bank of Tanzania from its foundation in 1966 to 1974, Minister of Finance from 1977 till Nyerere sacked him in 1979, and chairman of the political party CHADEMA from its foundation in 1992 until 1998.

Both Edwards and Lofchie situate what happened in Tanzania in terms of developments in economic theory, drawing on the seminal work of Robert Bates, also from Los Angeles, who explored various ways in which surpluses may be drawn from agriculture and invested in industry. Both are particularly critical of so-called “development economists”, even though they were the mainstream at the time, advised governments all over the world, with many of them awarded Nobel Prizes for economics. They were part of the movement inspired by Keynes which maintained growth and stability in Europe and America for at least 20 years after the Second World War; it was not unreasonable for them to conclude that industrialisation was an essential part of development, given that all countries which up to that time had achieved rapid growth, starting with the industrial revolution in Britain, but including the USA, Germany and Japan, and in a very different way the Soviet Union, had done so on the basis of industrialisation. Edwards briefly mentions the influence of the “dependency theorists” such as Samir Amin and Andre Gunder Frank; but not the ideas which derived from socialist economists such as Maurice Dobb, who criticised import substitution because they recognised that it would lead to continued dependence on inputs of semi-manufactured goods. The “basic industries strategy” of Tanzania’s Third Five Year Plan was an attempt to create the integrated economies achieved by the pioneers from the USSR or Japan – though the attempts at implementation bore little relation to the theory.

All three books include blow by blow accounts of the attempts to mediate between the IMF, who were insistent that devaluation was necessary from 1979 onwards, and Nyerere, who was determined to resist it. Nyerere was supported by Kighoma Malima, who moved from Minister of Finance to Minister of Planning and back to Finance. He was one of the first Tanzanian economists to get a PhD (from Princeton), but he was not alone. Papers opposing devaluation were written by Ajit Singh, from Cambridge England and Reg Green, by then at the University of Sussex. Devaluation was widely discussed in the Economics Department of the University of Dar es Salaam; the argument was that if the Bank of Tanzania controlled all allocations of foreign exchange, the Ministry of Agriculture set the prices paid to farmers for their crops, and the Price Commission set the prices for manufactured goods, it was not necessary to devalue since the government could set prices to give whatever economic signals it wanted. However, while that might be correct for an exchange rate slightly out of line with black markets, if you can get 4 or 5 times as many shillings for a dollar unofficially as legally, any such system is bound to break down. The reality was devastating: a parallel economy, often illegal or semi-legal, was quickly created; corruption broke out almost everywhere; and more and more of Tanzania’s trade was not shown in the official accounts.

Edwards describes the Tanzania he found when arrived in 1991: “There was almost no public transportation—people of every social condition walked for miles to get to work and back home—every road was an infinite collection of potholes, school children had no textbooks, blackouts were recurrent, there were (almost) no spare parts for machines or vehicles, and shops were almost empty. It seemed to me that the only cars that circulated belonged either to expatriate aid officials—most of them drove very large, shiny, four-wheel drives—to well-placed civil servants, or to high officials of the ruling party. In spite of the fact that there were basically no cars, there were parking meters in a number of downtown streets. Some were bent, most were rusting, and not one was operating. When I asked about them I was told that they were part of a donor’s project to deal with urban gridlock. I argued that there were no cars or buses and, thus, no traffic, let alone bottlenecks. The Treasury official that was with me smiled and said that the aid agency in question had concluded that, when it came to traffic jams, it was important to be proactive, to take preemptive measures.”

In this situation, as Lofchie shows, almost all Tanzanians on government salaries were forced either to seek bribes or to engage in “parallel activities” (i.e. some other way of making money) to survive. He points out that an over-valued exchange rate is very attractive for anyone who can get hold of foreign exchange, who can import goods, sell them at the unofficial rate, and then convert the resulting shillings to dollars at the official rate, and repeat the process. He suggests that this was exactly what large numbers of Tanzanians in senior positions did, and that it explains why the Bank of Tanzania ran short of foreign currency. However, little detail on this is provided; it is not clear if almost the whole ruling elite was complicit in this, whereas it might just have been a few big fish doing it on a grand scale, or even (in line with some of Aminzade’s descriptions) a few Asian businessmen.

It could not continue, and massive devaluations occurred from 1986 on, after Nyerere stood down as President. Import restrictions were removed. The currency found its own level. Exports rose, especially of gold but also of some manufactured items. Tourism flourished. And from about 2000 Tanzania had one of the fastest reported growth rates in the world. Lofchie’s political economy suggests that at some “tipping point” the interests of the elite changed from supplementing their incomes from corruption to earning profits from economic activity; the elite which at first opposed the reforms, then accepted them.

That is, if we can believe the figures. But Edwards in particular doubts the veracity of Tanzania’s economic statistics, especially for the subsistence and informal sectors. For example, in 2006, following a year of drought, for which declines in production were reported for many crops, agriculture as a whole was reported as growing at 4%. It is however, a little odd that he places this section of his book immediately after he has reported in depth using the official statistics – thereby joining other good company who have criticised Tanzania’s statistics while continuing to base their conclusions on them. But even official figures suggest that poverty remains a major issue, especially in the countryside, and that the benefits of rapid growth are flowing to the towns and cities, and to an elite within them.

All three writers discuss the promises of successive Presidents to resolve the issue of corruption, and the failures of any of them to have much impact. Aminzade provides the most detail about individuals and the involvement of Asians who were MPs or close to the administration (pp.337-349). Lofchie quotes the economist Jagdish Bhagwati who has argued that corruption can be beneficial if it undermines the siphoning off of resources through protection and an over-valued exchange rate. None of these writers quotes the broader discussions of Mushtaq Khan who points out that corruption can sometimes allow a single producer to get established in a market and become globally competitive, which may not happen if markets are completely open – pointing out that most of the Asian tigers, not least China, have well-documented high levels of corruption. Looking, finally, at the contributions made by these three books, Aminzade has read widely and his bibliography will make his book of great value for many years to come, though it is regrettable that the index does not include references to much of the material in his footnotes. He reports the views of journalists and MPs who had racialist stereotypes of both Asians and expatriates, and campaigned for a very rapid Africanisation. But Lofchie provides more detail as to why this did not happen. With hindsight this was surely for the better, because a country that gains independence with around 100 graduates cannot run hospitals, schools, railways, factories and the rest of public administration without outside help – and if it had tried would almost certainly have become a failed state.

Lofchie’s early chapters, in which he sets out his theory of an over-valued exchange rate and how this can enable a well off elite to improve their position, invite further research. Edwards has the greatest insider detail; but his dichotomy between aid before 1980 as toxic, and aid in more recent years as relatively benign, lacks detail. He criticises the Nordic countries, especially the Swedes, for supporting Tanzania in the Nyerere years; but aid for small industries such as a paper mill, forestry, rural water supplies and grain silos did not provide explicit support for villagisation or the use of force. The World Bank’s programmes to support the main agricultural crops, through subsidised inputs such as fertilizers, can be criticised on technical grounds but they were not tied to villagisation. Edwards’ claim (p.88) that the number of people living in villages was 9 million by 1975 and 13 million (nearly the whole population) by 1977 is sloppy; people living in the coffee producing areas did not move, nor in the cities. Lofchie’s figure of 1.6 million by the end of 1974 is nearer the mark.

Edwards gets carried away by the slogan of his title. The aid itself was not toxic: his real complaint (and fair comment) is that in the late 1970s the donors did not use their aid to put more pressure on the Tanzanians to review their policies of villagisation and excessive nationalisation. In the more recent period, as he points out, the donors have been vehement in their criticisms of corruption; but that has not led to much action by the Tanzanian government, or a withdrawal of the aid.

All three books lack a sufficiently robust theoretical underpinning. Thus Aminzade’s “contentious politics” is not sufficient to give direction and meaning to the mass of information he presents. “Toxic aid” without detailed studies of what that aid involved leaves the author open to wild swings in which aid was toxic in a period in which he compares Tanzania to countries in Latin America which also attempted socialist paths, but rather beneficial in a period when he finds the politics more congenial (even though the country is in real danger of being overcome by endemic corruption). Lofchie is right to attempt to use the tools of political economy, but lacks the detailed information to be sure that what he asserts as facts are not in reality well-informed surmises.

None of them discusses what could be the most contentious issue of all. If Tanzania wanted industries, it did not have to invite multinational companies to establish them. There was another option. Industrialisation had accelerated in the years before and after Independence. Much of it is still visible in the Chang’ombe area of Dar es Salaam, where many Asian-owned businesses either processed locally produced raw materials or supplied consumer items. If the Tanzanian leadership had worked closely with this group, as it did with a few individuals, such as Andy Chande, it would not have had to find the capital or supply the protection demanded by multinational companies. Aminzade would no doubt argue that this would have been politically unthinkable. Lofchie might also argue, from his knowledge of race relations, that this would be a difficult policy to sell to the Tanzanian people. But joint work with this group could have led rapidly to the creation of a Tanzanian business class. Even now businesses such as these are contributing substantially to Tanzania’s rising exports of manufactured goods to neighbouring African countries. They should not be almost entirely written out of the story.

Andrew Coulson

Andrew Coulson worked in Tanzania first in the Ministry of Agriculture and later in the Department of Economics at the University of Dar es Salaam. Since 1984 he has worked at the University of Birmingham. A second edition of his book Tanzania: A Political Economy was recently published by Oxford University Press. He is Vice-Chair of the Britain Tanzania Society.

THE NATURE OF CHRISTIANITY IN NORTHERN TANZANIA: ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL CHANGE 1890-1916. Robert B. Munson. Lexington Books ISBN 978 0 7391 7780 8 h/b pp378. £70.00.

This book is an exploration of the introduction of new plant species by missionaries in German East Africa, and the effect this had on the spread of Christianity among people of Chagga, Meru and Arusha ethnicities around Mt Kilimanjaro and Mt Meru, This is an area that attracted Protestant missionaries, such as the Leipzig Mission, as well as Catholics known as the Spiritans. The timeframe of the book is that of German colonialism, and the work makes extensive use of German archival sources. Indeed, one of the greatest values of a work such as this is making these sources available to an English-speaking audience.

The title is unfortunate and does not reflect the content, as it is not clear that it is a pun: “the nature of Christianity” refers to the nature (i.e. plants) introduced by Christian missions.

The new plants brought to the landscape, Munson argues, went hand-inhand with Christianity . He calls this botanical proselytization, a term that “emphasizes the mutual dependence of the landscape, botanical and Christian changes”. His argument is based on a view of African religion that is all-inclusive, with no division between the sacred and secular; thus, the “landscape changes reinforced the Christian worldview and vice versa, strengthening and deepening each in turn.”

The origins of the work as a PhD thesis are clear, yet the writing style is engaging. Unfortunately, the dozen photographs are badly reproduced. The book places the evolution of the missions in the context of German imperial attitudes towards its colony, arguing that the Maji Maji rebellion in the south made the Germans more aware of the impact that their policies were having. The next chapters focus on three central themes – Places, Plants and People. In exploring place, the author examines the spatial transformation of landscape through surveying, producing maps and establishing forest reserves to divide “people” from “nature”. In one of the most interesting sections he also explores the establishment and development of Moshi and Arusha.

Turning to plants, the book examines the botanical introductions made by the missionaries, and how they were integrated into African society. He goes beyond the usual discussion of coffee to explore various species of tree and the potato. The chapter entitled “People: Christianity and Botanical Proselytization” explores how the introduction of Christianity led to social change.

A short final chapter briefly outlines the changes since the British took control of the region in 1916, but in effect this raises more questions than it answers. An inherent problem with the book is the abrupt end of German rule; the consequences and impact of the subsequent botanical and social changes fall outside of the timeframe of the work. The tight focus enables greater historical depth, but more direct engagement with a broader theoretical literature would have been welcome. A more detailed exploration of theories of appropriation, for example, would have given the work relevance beyond the region it covers. As it stands, the work is a valuable contribution to the history of northern Tanzania.

Tom Fisher

Tom Fisher has a PhD from the University of Edinburgh exploring politics and ethnicity in Kilimanjaro. Until recently he lectured in history at St Augustine University of Tanzania, Mwanza.

A FIELD GUIDE TO THE LARGER MAMMALS OF TANZANIA (PRINCETON FIELD GUIDE 2014). Charles and Lara Foley; Princeton University Press 2014 320pp £19.95 (pb).

After spending a good few years working in the field of African conservation and tourism, it is normally difficult to get excited about the release of a new field guide; after all, how different can it be? But not this time, as the new Field guide to the larger mammals of Tanzania is an excellent addition to the literature and is a ‘must buy’ for both seasoned safari-goer and first-timer.

The authors behind this edition are all practising ecologists with a great many years of experience working in the national parks and protected areas of Tanzania. What is evident is that they know what previous field guides were missing. This book has been structured in a way that makes it easy to use, both when grabbed quickly in the back of a Land rover or when consulted at leisure in the cool of your tent. Most importantly, the ongoing challenges and threats to the long-term conservation of the species included remain clear throughout.

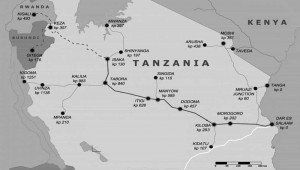

The bulk of the book is made up of ‘Species Accounts’, each of which lists the common, scientific and Swahili names; a species description; notes on similar species: ecology and social behaviour; distribution in Tanzania ; population size and conservation status assessment; a distribution map and colour images. The images are particularly useful as they are a mixture of professional photographs and images produced by camera-traps, which display the animals as the safarigoer may have seen them.

The guide concludes with quick-reference species images complete with essential diagnostic data and an introduction to the major national parks and protected areas of Tanzania (complete with species list).

So whether you are into the big cats, primates or whales, this guide is for you. Finally, all author royalties received from the sale of this book will be donated to the Wildlife Conservation Society and used to support the Tanzania Carnivore Project or other wildlife conservation projects in Tanzania.

Mark Gillies

MANAGING TAX REGIMES IN TANZANIA: EXPERIENCES, CHALLENGES AND LESSONS. Edited by Harry Kitillya, Tema Publishers, P O Box 63115, Dar es Salaam, 2014.

TANZANIA GOVERNANCE REVIEW 2012: TRANSPARENCY WITH IMPUNITY? Policy Forum, P O Box 38486, Dar es Salaam, 2013.

STATISTICS IN THE MEDIA: LEARNING FROM PRACTICE.

Karim Hirji. Media Council of Tanzania, 2012. These three publications from Dar-es-Salaam will be of interest to researchers. In the first, Harry Kitillya (Commissioner General of the Tanzania Revenue Authority from 2003 to 2013) has commissioned a set of articles to provide a bible of information about all aspects of tax collection in Tanzania. Overall the authors are well informed and optimistic – though no doubt more could be said about tax avoidance and especially about corruption in the tax gathering regime. Transparency with Impunity surveys the state of governance and corruption in Tanzania. Almost all aspects of government activity are covered. The tables, charts – and the cartoons – draw on an exceptionally wide range of official and NGO publications. This report should be a major source for researching the Tanzanian economy.

Statistics in the Media is a study of the misuse of statistics written as teaching material for journalists and to provide them with an introductory text in basic statistics. Much of it is constructed around topical case studies of exam results, alternative medicine, deaths from malaria etc. The author suggests that the resulting bias is not random, but reflect or reinforce the interests of those who own the media.