Edited by John Cooper-Poole (UK) and Marion Doro (USA)

TANGANYIKA DIAMOND PRESENTED TO PRINCESS ELIZABETH, Jarat Chopra, Old Africa, No. 21, February/March 2009, pp. 16-17. The Old Africa website, which describes the journal, is: http://oldafricamagazine.com/

IC Chopra Presents Pink Diamond to HRH Princess Elizabeth in 1948 , photograph courtesy of Jarat Chopra

A recent article in Old Africa by Jarat Chopra will be of interest to our readers. Jarat is the grandson of The Hon Iqbal Chopra K.C., Member of the Legislative Assembly, who was the partner of J.T.Williamson in the Mwadui diamond mine. The two men were very different in character; Williamson the self-effacing geologist who made the crucial discovery, and Chopra the extrovert man of affairs who arranged the finance, kept officialdom and potential rivals at bay and ensured that control remained with the two partners.

This short but very interesting article tells the story of the partnership, and also of the legendary pink diamond which the partners gave to the then Princess Elizabeth as a wedding present, on behalf of the people of Tanganyika. Characteristically the actual presentation was made by Chopra who always revelled in the limelight, rather than by Williamson who preferred to remain behind the scenes. It all seems so long ago, and yet Chopra tells me that his family’s two Rolls Royce’s, which were a feature of the Mwanza scene in the 1970’s are still around. As, of course, is the former Princess Elizabeth!

J.C-P.

THE POVERTY AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2007

A FRAMEWORK FOR A TANZANIAN GROWTH STRATEGY

VIEWS OF THE PEOPLE 2007

THE IMPACT OF REFORMS ON THE QUALITY OF PRIMARY EDUCATION IN TANZANIA

THE ROLE OF SMALL BUSINESS IN POVERTY ALLEVIATION: THE CASE OF DAR ES SALAAM

REALISING WATER POTENTIAL TO SUPPORT GROWTH IN TANZANIA

All available from Research on Poverty Alleviation (REPOA) P.O. Box 33223, Dar es Salaam. www.repoa.or.tz. repoa@repoa.or.tz

Although it is hard to pick out a number of clear and concise themes from such a wide ranging series of documents, it is possible to perhaps draw out a few strands about what they imply for modern day Tanzania. The starting point seems to be that although there has been a sharp pick up in the overall growth rate since the mid-1990s, results of the 2007 Household Budget Survey (HBS), which provides the majority of the hard data for the Poverty and Human Development Report 2007, show the impact of this on the average person has been limited. In fact, this is the fourth country specific Human Development Report and the third HBS, and all tend to confirm that despite the pick up in the GDP growth rate there has still only been a marginal impact in reducing poverty.

But they also show that it is not all bad news. There has been significant progress by thousands of individuals in improving the quality of housing for example, with sharp increases in the use of metal roofs, non-earth floors and more durable walls. There has also been a sharp increase in the ownership of various consumer goods, led by mobile phones, in all parts of the country, but also bicycles and mosquito nets in rural areas. However, the overall implication still seems to be that the growth rate is not high enough to have a sustained and deep impact on poverty.

Another important theme of the research seems to be how mixed the impact of rising government spending has been in terms of delivering government services to poor households. In particular, although the number of children attending school has increased there are still deep concerns about the quality of the education provided. Perhaps even more worrying, there has been virtually no change in access to health care, while access to water supplies has worsened in the last decade. This latter statistic is particularly worrying, as it comes at a time when a number of other studies have shown the huge potential impact of improving water and sanitation. Apparently simple measures such as installing toilets and providing safe water supplies have the potential to do more to end poverty and improve health than any other intervention.

The neglect of water and sanitation also highlights another theme across the documents. While donors can have a positive impact, they tend to focus on a limited number of areas at one time. In recent years this has been the provision of free education because this provides an easy to achieve target – hence progress on this front, if not on the quality of what is being taught.

But they back away from other issues such as water sector reform once they seem too complex. This certainly seems to be the case in Tanzania, where donors supported the award of a ten year management contract for the Dar es Salaam Water and Sewage Authority (DAWASA), but when this fell apart in 2005 did not seem to have a back-up plan to support investment in the sector in a rapidly growing city, other than to re-establish what was arguably a failing parastatal, but with the new name, the Dar es Salaam Water and Sewage Corporation, and to engage in prolonged legal action with the consortium that had been awarded the management contract – City Water.

The other theme is that when governments and donors fail to provide services, or if the business environment is too bureaucratic as is the case in Tanzania, informal small scale businesses step into this vacuum. As the HBS data shows, although the number of households with access to piped water in Dar es Salaam fell from 86% in 2000/01 to only 58% in 2007, there has been an increase in access to “other protected sources”. But in an unregulated environment this can have a major cost. The rise of unregulated providers of “non-protected sources” has led to scandals about the quality of water supplies, with some private sector suppliers claiming they are providing clean water, when tests show this is clearly not the case. Moreover, the city’s traffic problem is clearly compounded by the growth in privately owned tanker lorries which ferry water into the city from the surrounding regions.

How are these trends viewed by the average Tanzanian? In the Views of the People the surveyors asked 7,879 Tanzanians aged between 7 and 90 years old in ten provinces around the country their views on a wide range of economic and governance issues. The broad finding was that 24% argued that their economic situation had improved; 26% reported no change, while the other half estimated that their living standards had deteriorated. The main economic concerns of those questioned related to the poor state of infrastructure, especially roads if they lived outside of Dar-es-Salaam. But as with the HBS the findings were not all negative. For example, although the rising cost of food was said to be a problem by 67% of adults surveyed, the survey also found that 47% also claimed they had not had a problem with eating enough food in the last year, while 63% stated they ate three meals a day (this proportion rose to 78% in Dar es Salaam).

Where does this leave the government? From their end it does seem that there is a need to really join up the dots and develop a coherent framework on what needs to be done to drive growth and to get donors to fit into this. All parties would probably claim they are committed to this. In fact, this is the point of the Growth Strategy which seeks measures along these lines to try and push the growth rate up to 8-10%. But the reality is that progress has been slow and that talk of cooperation is greater than actual cooperation. Meanwhile, the rate of improvement is very slow, while expectations amongst the general population that their lives should be improving are rising more quickly. It is this gap that needs to be closed, and closed quickly.

David Cowan

IMAGINING SERENGETI: A HISTORY OF LANDSCAPE MEMORY IN TANZANIA FROM EARLIEST TIMES TO THE PRESENT. Jan Bender Shetler. New African Histories series, Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio, 2007. xiv + 378pp. ISBN-10 0-8214-1750-9, ISBN-13 978-0-8214-1750-8. (paperback) £25.50

As my copy of a popular guide book says, the Serengeti needs little introduction. It is “one of the world’s most famous wildlife areas” and, thanks to “the largest mammalian migration on earth”, occupies a “hallowed place in our imagination”. What The Rough Guide doesn’t say is that the landscape of the Serengeti plays a very different role in the historical imagination of the people who live around it, but whose access to Serengeti National Park and associated protected areas is now severely limited. As consumers of wildlife and wildlife documentaries it is easy for us to forget that the “natural zoos” that we or the cameras are travelling through were once lived in and used by local people, many of whom have been removed or excluded against their will from the landscapes that still bear the names of their ancestors.

Jan Bender Shetler’s Imagining Serengeti is an ambitious attempt to restore local voices to their proper place in regional history, a study of the peoples of the western Serengeti and their narratives about the past from the “earliest times to the present”. It is based on the long-term research among the Bantu-speaking Ikoma, Nata, Ishenyi, Ikizu and Ngoreme of Serengeti and Bunda Districts in the south-eastern corner of Mara Region, and also draws in the history of other past and present users of the Serengeti, including the Kuria and Sonjo, and the Nilotic-speaking Tatoga and Maasai. In addition to material collected in the field the author has made extensive use of the available archives and published literature, and a full third of the book is taken up with the scholarly apparatus of glossary, notes, bibliography and index. It is also well illustrated, with a number of well-drawn maps and black and white photos.

Following a lucid introduction to “Landscapes of Memory” and the approach to social history which frames the book, the rest of the main text is divided into two parts, the first about historical memory before the 19th century, the second about the period after. Part I, “Past Ways of Seeing and Using the Landscape”, comprises separate chapters on “Ecological”, “Social” and “Sacred Landscapes”, focusing respectively on traditions of origin, clan histories, and histories of ritual and sacred sites. Part II, “Landscape Memory and Historical Challenges”, opens with a chapter on “The Time of Disasters” and includes an account of the ecological “collapse” that came in the wake of Maasai raiding and the penetration of global trade networks. This is followed by chapters on “Resistance to Colonial Incorporation” and the “Creation of Serengeti National Park”, describing how the peoples of the western Serengeti were excluded from the park and labelled as “poachers”, and concluding – as other critics have done – that recent community-based conservation initiatives have led to greater state control and provided limited benefits to the local population.

The book’s conclusions, “Imagining Serengeti History”, are squeezed into four pages at the end of the final chapter. To me this hurried ending is a bit of a let-down after being told in the introductory chapter that Imagining Serengeti “adds both a rich, new dimension to existing conversations about preserving African environments and a new methodological approach to precolonial African history.” There are a number of immodest statements of this kind at the beginning of the book, and they only serve to highlight the weakness of its theoretical pretensions. Although the author strives to link each chapter and each period of western Serengeti historical imagining to the use of different “core spatial images” (in the second half of the book these are “loss and dispersal”, “hiding and subterfuge”, and “constriction and restriction”), a less charitable view would see these as narrative tropes of her own invention that have been tacked onto the study in a misguided attempt to give it an analytic structure and added intellectual weight.

This is unnecessary. Imagining Serengeti is based on an impressive amount of scholarship and represents an important contribution to the social and environmental history of northern Tanzania. While reading it I wanted more: in the first half, for example, the further use of historical linguistic data to build upon and perhaps challenge general conclusions borrowed from Ehret, Schoenbrun and others; in the second half more detail about ongoing struggles over access to protected areas and the utilisation of natural resources, a subject which deserves its own full-length study.

But other than imagining a different book, I spotted relatively few mistakes in this one. The botanical name of the tree which provided arrow poison (obosongo) is misspelt in both the text and index, and should be updated to Acokanthera schimperi (A.DC.) Schweinf. (syn. A. friesiorum Markgr.). The standard abbreviation for Tanzania National Parks is TANAPA, not TNP. And something is missing from the first sentence of the second paragraph on page 31.

Martin Walsh

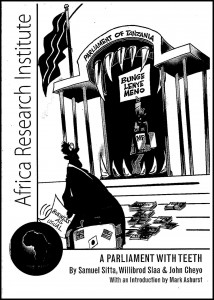

A PARLIAMENT WITH TEETH by Samuel Sitta, Willbrod Slaa and John Cheyo with an introduction by Mark Ashurst. Africa Research Institute. 43 Old Queen Street, London SW1H 9JA. ISBN 978 1 906329 02 0

To paraphrase President Obama – Yes it has. Tanzania’s parliament has got teeth, and, as explained succinctly by House of Assembly Speaker Samuel Sitta, in this short, very readable, 88 – page book, the teeth have grown or been implanted largely within the last two years. He writes ‘For the first decade after independence, Parliament was quite robust. People who came from areas where there were strong chieftains tended to be ‘rightists’. The younger generation, who studied in Cuba, tended to be ‘leftists’.

People stood for issues. During the 1980s and 1990s party loyalty became more important. If you had different ideas you were looked upon us unpatriotic. Nothing really changed when the multi-party constitution was first introduced in 1992. The CCM, the majority party, still acted as if Tanzania was a one-party state.

However, the most recent changes include much greater independence for parliament. It no longer acts as an appendage of the Prime Ministers Office. It also has financial independence for the first time and is now able to receive money direct from external donors. The World Bank has provided $19 million. More importantly, the House Standing Orders have been revised and the Prime Minister now has to come to Parliament to answer questions. Sitta writes that there is a new mood in parliament, an appetite to get things done in a different way. It is now possible for the first time to appoint select committees to investigate controversial issues such as the Richmond corruption case (see above).

The second contributor is the opposition’s Dr Wilbrod Slaa, who must be becoming Tanzanian’s most well known legislator as he tirelessly pursues more and more cases of alleged corruption. He discusses how he thinks there will be, eventually, a change in the power structure in parliament and how the all powerful CCM party might eventually be defeated in elections to parliament. He also writes about foreign donors: ‘70% of government purchases are financed almost entirely by donors. Donors pay our salaries as MP’s.’ He suggests ways of improving relations between parliament and donors.

John Cheyo MP, who is Chairman of parliament’s Public Accounts Committee, explains the changes brought about by the Public Audit Act of 2008 and how its first report was longer (450 pages) than usual, produced on time and was taken much more seriously by the President and others. MP’s were beginning to ‘clean up the old system.’

In its final recommendations the authors seem to agree on the fundamentals about what needs to be done in future but differ on some of the details. The longest single section of the book is an excellent introduction, full of insight, by Mark Ashurst, Director of the Africa Research Institute which should be compulsory reading for those new to politics in Tanzania and also to those who already know a lot but need to up-date themselves. He is right in concluding that ‘a strong executive needs a vigilant parliament. The best prospect of a strong leader is a parliament with teeth.’ D.R.B

Illustration from the cover of the “Dogodogo” book

Illustration from the cover of the “Dogodogo” book